I’ve gotten positive feedback about a post in which I explain how it’s not that much work for me to do active learning in the classroom. However, a couple entirely reasonable misgiving seem to crop up, and I’d like to give my take on those causes for reluctance to start up with active learning approaches. Continue reading

communication

Where do you eat lunch? And does it matter?

StandardLunch culture seems to vary a lot from place to place.

I will admit to sometimes eating lunch at my desk, even though it is seems a highly unusual thing at European universities. But these days it is rare for me to do that, partly because most people aren’t and partly because it is just nicer to take a moment and eat properly. Continue reading

Dealing with devices

StandardDistractions in the classroom are a problem.

Digital devices are often a huge distraction.

Therefore, to manage distractions in the classroom, we need to manage devices.

Remetaphoring the “academic pipeline”

StandardWe need to ditch the “academic pipeline” metaphor. Why?

The professional destinations of people who enter academic science are necessarily varied.

We do not intend or plan for everybody training in science to become academic researchers.

The pipeline metaphor dehumanizes people. Continue reading

Respectful conversation at academic conferences

StandardYou’re probably familiar with this scene from academic conferences:

Person A and and Person B have been chatting for a few minutes. Person C strolls by and makes eye contact with Person A. Person C gives a big smile to Person A, which is reciprocated, perhaps with a hug. Both A and C enthusiastically ask one another about their lab mates, families, and life in general.

At this moment, Person B is feeling awkward.

Journalistic bias in Science Magazine

StandardThere was a piece published on the Science Magazine website, by Eli Kintisch, that smelled fishy to me. The article was an overview of a range of efforts to make the sharing of raw scientific data easier and more common. Continue reading

Huge problems during research are totally normal

StandardAt the moment, I have the great pleasure of working with a bunch of students at my field site in Costa Rica. Which means that I’m really busy — especially during the World Cup too! — but I’m squirreling away a bit of time before lunch to write about this perennial fact that permeates each field season.

We are used to stuff working. When you try to start your car, it turns on. When we set alarms to wake us up, they typically wake us up. You take a class, work hard and study, and earn a decent grade. Usually these things things happen. And when they don’t happen, it’s a malfunction and a sign of something wrong. Continue reading

Preparing a talk for a conference

StandardI distinctly recall a little non-event at a conference: I was scooting to catch a friend’s talk on time. I found him sitting in the hallway outside the room, slide carousel* in his lap. Grabbing a bunch of slides and putting them into his carousel. He was picking out slides, on the fly at literally the last minute. Figuring out both his content and his sequence Continue reading

The interplay of science and activism

StandardThis is a guest post by Lirael.

I’m a grad student in the sciences. I’m also an activist. I spend most of my time doing one of those two things. So Amy’s recent post got me thinking about science and activism and how they mix. What do you do when needed public attention to some issue in your field turns out to be lacking in scientific literacy (or understanding of the business of science)? How, in general, do science and politics interact? What are the implications of those interactions?

When we talk about making things political, what we typically mean is reducing them to soundbites or partisan battles. But if you think of politics in a broader sense, most things are political, or at least have political implications, including science. Study on the speed and potential effects of climate change is political. Which diseases get prioritized in research funding is political. How diseases are defined is political (look up the controversy around women, the CDC, and AIDS in the early 1990s). Robotics, with its wide variety of applications, including politically charged ones like defense, manufacturing, and agriculture, is political. Politics is about people’s lives, and science affects people’s lives – isn’t that one of the reasons that many of us got into it?

Funding isn’t apolitical either. Within some fields of math and computer science, there’s significant controversy about NSA funding. One reason that I stopped working for defense contractors was my discomfort with how the funding source affected how we were thinking about the potential applications of our own work – for instance, thinking of, and presenting, work on fast pattern classification in terms of its usefulness in missile guidance rather than its usefulness in classifying ventricular arrhythmias or diagnosing retinal disorders. Or thinking of and presenting work on indoor robot navigation in terms of military applications rather than civilian emergency assistance, room cleaning, etc. And concerns about funding and conflicts of interest, especially in a biotech context, leading to bad/biased science aren’t limited to people who are clueless about how science funding works.

The Avaaz campaign pitch has a lot of cluelessness, as we’ve noted. They don’t seem to get how science is done – they think they’re going to change the field by funding a single study? They don’t consider how their funding might be just as likely to introduce bias into the science that they fund as any other funding. They don’t explain how they’re going to find a lab to fund. They don’t appear to know the state of bee research very well, or if they do, they’ve sacrificed that in the name of a more easily accessible funding pitch. So what do scientists do with this? What do activists do with this? What’s a better model than this campaign? What can we do to help ensure that people who are committed to action on the problems that affect their lives understand the science behind it?

I’ve been active in my state’s climate justice movement over the last year, and one of the things that struck me was how many scientists there were at the protests. I’ve participated in a lot of social movements, and let me tell you, that is not something that you usually see. There was a time when I was in a group doing jail support (where you wait outside a jail for arrestees to be released so that you can give them food and water and first aid and emotional support), and a tenured physicist, who was also part of the jail support group, gave an impromptu lecture on introductory thermodynamics to a group of interested fellow protesters to pass the time. I’ve gotten rides to events with people who tell me about their research in geology or atmospheric science. One of the major local organizers is on leave from a math PhD program. I’ve been on a six-day march where one evening, after we got to our camp site, we sat around and had a Q&A with a photovoltaics guy about the current state of solar energy. These people add a lot to the movement. They participate in a variety of ways, and they also educate. The climate justice movement has been bringing scientists to teach-ins, to improve other participants’ scientific literacy, for years.

Another interesting model is the Union of Concerned Scientists , which started as a project of MIT students and faculty in 1969. They produce layperson-friendly issue briefings (including on science funding as well as on relevant science and engineering issues themselves), produce original research and analysis, run scientifically-literate petition campaigns, and much more. Many of their issue briefings contain “What You Can Do” pages for laypeople, and they have an activist toolkit on their site.

Layperson activists can play important roles in the politics of science. In the first example that pops into my head, the often-confrontational AIDS action group, ACT UP, which was not exactly known for its nuance, won lower prices per patient for AIDS treatments, accelerations in FDA review of treatments, and improved NIH guidelines for clinical trials. Were there ACT UP participants who reduced complex issues of funding, safety, and research pace, to simplistic talking points? Yes. Did they sometimes say things that were unfair to well-meaning scientists? Probably. But they got results – working together with scientist-activist mentors like organic chemist Dr. Iris Long.

If you think that a movement is trying to support a worthy cause but is missing important points (or making wrong ones) with their sloganeering, help them come up with better slogans (yes, you need slogans, not just journal articles, in any form of activism) and better talking points.

Our expert advice remains unheeded

StandardOnce in a while, tropical biologists get bot flies. We sometimes find this out while were are in the field. But on five occasions, my students have returned to the US, and then discovered that they are hosting a bot. They all contacted me for advice. I told them a few things, but the most important one was:

Whatever you do, don’t go see a doctor. That could be disastrous.

Nonetheless, three of these students went to the doctor.

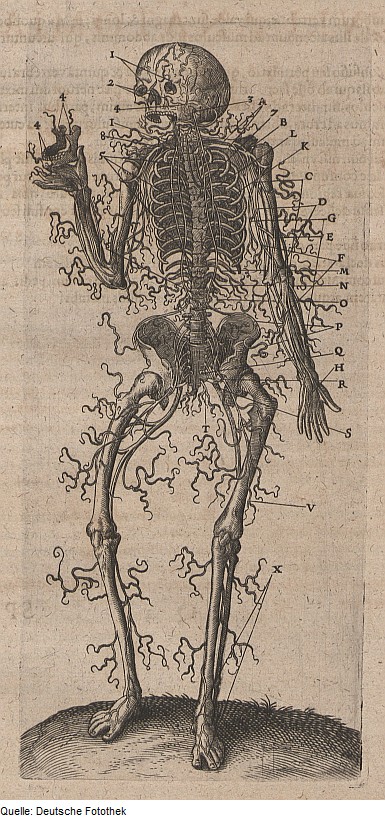

A mature bot fly larva, Dermatobia hominis, that emerged from my student’s arm while he was sleeping. He intentionally reared this one out and allowed it to pupate. Pencil is for scale. Photo: T. McGlynn

This has always troubled me. Without any additional context, it looks like the students just didn’t trust me, and thought that I’m stupid. At the very least, it shows that they trusted their own intuition over my recommendation based on a long history of experience. It shows that they followed the misinformed advice of family and friends over the judgment of the person who was responsible for the trip to the rainforest.

It shows that when it really really really counts, my guidance ain’t worth much at all to my own students.

I don’t give students this instruction without an explanation. I tell them that nearly every doctor in the US will want to cut the creature out. History shows that bot fly larvae are smarter than doctors. If you present yourself to a US doctor with a bot inside you, the predictable result is that you leave the doctor with your bot inside you. You will also leave without a large chunk of flesh that the doctor removed in a futile attempt to get the bot. Sometimes the bot is killed in the surgery, but not excised, which leads to a rotting carcass and infection, and the need for serious antibiotics. I tell them that, if they can’t get it out using the variety of techniques we’ve discussed, and they feel compelled to go to a medical professional, they must go to a vet and not to a doctor. (The students who did the opposite of my recommendation came to regret their choice, if you’re wondering.)

These bot fly incidents are convergent with a recurring incident in a non-majors laboratory that I have taught. The week before an exam, I hand out a review sheet that specifies the scope of the exam. I then tell the class:

Check out item number three on the review sheet. This is a straightforward question about osmosis. The answer is that the volume of water in the tubing will “increase.” The correct answer to this question is “increase.” Just circle the word “increase” and do not circle the word “decrease.” I’m letting you know the answer to this question now and I guarantee — the odds of this question being on the exam next week are 100%. I promise to you, with all of my heart, that this question will be on the exam word for word, and this one question will be worth 20% of your grade on this exam. You don’t want to get this question wrong, and I’m telling you about it right now. So, be sure to write down in your notes that this question will be on the exam and be sure to remember the correct answer when you see it.

The reason that I’m being really obvious about telling you about this question its that in the past, half of the class has gotten the answer to this question wrong. It’s a simple question, and it addresses the main point of the lab we conducted for more than two hours last week, but still, lot of people got it wrong last semester.

You should know that those students also were told in advance what would be on the exam. Just like I’m telling you right now. They knew that 20% of their exam hinged on remembering one word, “increase,” and still the majority of them got it wrong. I’m telling you this now because I don’t want you to suffer the same fate of those other students. DON’T BE LIKE THE STUDENTS FROM LAST SEMESTER WHO WERE FED THE ANSWER AND THEN GOT IT WRONG THE FOLLOWING WEEK. Just remember that “increase” is correct and the other word is not correct. I’d like you to remember the physical mechanism that explains this osmosis, but more than anything else I’d like you to demonstrate that you can be prepared for the exam and remember this small fact which I am hand-feeding to you right now. I promise to you this exact question will be on the exam Learn from your predecessors, don’t make their mistake. I’m giving you 20% of the exam for free right now, so write this down.

As I give this slightly overwrought speech, the students are paying attention. There is eye contact. They might be note-taking activity. Nobody’s on their phone, and nobody’s chitchatting.

When I administer the exam, more than half of the class circles “decrease” instead of “increase.” This has happened four times, and each time it happens a little piece of my heart dies.

As you can imagine, many of the students in our non-majors class are as disengaged as humanly possible. By no means is this a difficult course, even with low standards, but the fail rate for the corresponding lecture course is about 50%. The students who fail are clearly doing so because they aren’t even making the slightest effort. The reason that I keep giving students that same question over and over, and give them the correct answer over and over, is to give me some reassurance that the wretched performance by so many of the students is not my fault. I do this to grant myself absolution.

In these labs, each week is designed to give students the opportunity to develop their own experiments, find new information on their own, and work together to solve problems. This happens to some degree. But half of the students do not exert the tiniest amount of thought about doing what it takes to pass the exam. Why don’t they even try even the slightest, despite my best efforts to both inspire and feed them the right answers?

The students who fail these exams trust their own intuition, or some other model of behavior, instead of my own advice. If anybody is the person to tell you how to pass the exam, it should be the professor who is telling you the answers to the exam. But in this case, the students weren’t even bothering to look at their notes for five seconds before stepping into the exam. They’ve presumably heard from other people that work is not required for this class whatsoever, or perhaps they don’t care for some other reason. All I know is that no matter what I do, I can’t get these students to care about their grade on the exam. Some are excited about the labs, but not necessarily in passing.

So, what do the bot fly story and the osmosis story have in common? No matter how hard we try, sometimes our students won’t follow our recommendations. At least, not mine.

We are fancy-pants PhD professors, with highly specialized training. We’re paid to be the experts and to know better. That doesn’t mean that our words are prioritized over other words. Anything we might say just ends up in a stream of ideas, most of these ideas just flow out as easily as they flow in. It’s no accident that my teaching philosophy is “you don’t truly learn something unless you discover it on your own.” This is why I focus on creating opportunities for self-discovery in teaching. This is the only way in which people truly learn.

No matter what we professors might say or do about bot flies, or studying for exams, or anything else, other people will rely on their own judgment over our own. Even when the experts are overtly correct on the facts, even smart people often use misguided intuition when making important decisions, even when they are obviously wrong on the facts and the experts are overtly correct.

It’s easier to listen to other people than it is to heed their words. As a professor and research mentor, I’ve given up on the expectation of being heeded. I just work to speed up the process of self-discovery of important ideas. But, for the most part, I still don’t know how to do that. I think it’s an acquired skill, and a craft, and I think I still have a ways to go.

Why I prefer anonymous peer reviews

StandardNowadays, I rarely sign my reviews.

In general, I think it’s best if reviews are anonymous. This is my opinion as an author, as a reviewer, and as an editor. What are my reasons? Anonymous reviews might promote better science, facilitate a more even paying field, and protect junior scientists.

The freedom to sign reviews without negative repercussions is a manifestation of privilege. The use of signed reviews promotes an environment in which some have more latitude than others. When a tenured professor such as myself signs reviews, especially those with negative recommendations, I’m exercising liberties that are not as available to a PhD candidate.

To explain this, here I describe and compare the potential negative repercussions of signed and unsigned reviews.

Unsigned reviews create the potential for harm to authors, though this harm may be evenly distributed among researchers. Arguably, unsigned reviews allow reviewers to be sloppy and get away with a less-than-complete evaluation, which will cause the reviewer to fall out of the good graces of the editor, but not that of the authors. Also, reviewer anonymity allows scientific competitors or enemies to write reviews that unfairly trash (or more strategically sabotage) the work of one another. Junior scientists may not have as much social capital to garner favorable reviews from friends in the business as senior researchers. But on the other hand, anonymous reviews can mask the favoritism that may happen during the review process, conferring an advantage to senior researchers with a larger professional network.

Signed reviews create the potential for harm to reviewers, and confer an advantage to influential authors. It would take a brave, and perhaps foolhardy, junior scientist to write a thorough review of a poor-quality paper coming from the lab of an established senior scientist. This could harm the odds of landing a postdoc, getting a grant funded, or getting a favorable external tenure evaluation. Meanwhile, senior scientists may have more latitude to be critical without fear of direct effects on the ability to bring home a monthly paycheck. Signed reviews might allow more influential scientists to experience a breezier peer review experience than unknown authors.

When the identity of reviewers is disclosed, these data may result in more novel game theoretical strategies that may further subvert the peer-review process. For example, I know there are some reviewers out there who seem to really love the stuff that I do, and there is at least one (and maybe more) who appear to have it in for me. It would only be rational for me to list the people who give me negative reviews as non-preferred reviewers, and those who gave positive reviews as recommended reviewers. If I knew who they were. If everybody knew who gave them more positive and more negative reviews, some people would make choices to help them exploit the system to garner more lightweight peer review. The removal of anonymity can open the door to corruption, including tit-for-tat review strategies. Such a dynamic in the system would further exacerbate the asymmetries between the less experienced and more experienced scientists.

The use of signed reviews won’t stop people from sabotaging other papers. However signed reviews might allow more senior researchers to use their experience with the review system to exploit it in their favor. It takes experience receiving reviews, writing reviews, and handling manuscripts to anticipate the how editors respond to reviews. Of course, let’s not undersell editors, most of whom I would guess are savvy people capable of putting reviews in social context.

I’ve heard a number people say that signing their reviews forces them to write better reviews. This implies that some may use the veil of their identity to act less than honorably or at least not try as hard. (If you were to ask pseudonymous science bloggers, most would disagree.) While the content of the review might be substantially the same regardless of identity, a signed review might be polished with more varnish. I work hard to be polite and write a fair review regardless of whether I put my name on it. But I do admit that when I sign a review, I give it a triple-read to minimize the risk that something could be taken the wrong way (just as whenever I publish a post on this site). I wouldn’t intentionally say anything different when I sign, but it’s normal to take negative reviews personally, so I try to phrase things so that the negative feelings aren’t transferred to me as a person.

I haven’t always felt this way. About ten years ago, I consciously chose to sign all of my reviews, and I did this for a few years. I observed two side effects of this choice. The first one was a couple instances of awkward interactions at conferences. The second was an uptick in the rate which I was asked to review stuff. I think this is not merely a correlative relationship, because a bunch of the editors who were hitting me up for reviews were authors of papers that I had recently reviewed non-anonymously. (This was affirmation that I did a good job with my reviews, which was nice. But as we say, being a good reviewer and three bucks will get you a cup of coffee.)

Why did I give up signing reviews? Rejection rates for journals are high; most papers are rejected. Even though my reviews, on average, had similar recommendations as other reviewers, it was my name as reviewer that was connected to the rejection. My subfields are small, and if there’s someone who I’ve yet to meet, I don’t want my first introduction to be a review that results in a rejection.

Having a signed review is different than being the rejecting subject editor. As subject editor, I point to reviews to validate the decision, and I also have my well-reasoned editor-in-chief, who to his credit doesn’t follow subject editor recommendations in a pro forma fashion. The reviewer is the bad guy, not the editor. I don’t want to be identified as the bad guy unless it’s necessary. Even if my review is affirming, polite, and as professional as possible in a good way, if the paper is rejected, I’m the mechanism by which it’s rejected. My position at a teaching-focused institution places me on the margins of the research community, even if I am an active researcher. Why the heck would I put my name on something that, if taken the wrong way, could result in further marginalization?

When do I sign? There are two kinds of situations. First, some journals ask us to sign, and I will for high-acceptance rate journals. Second, if I recommend changes involving citations to my own work, I sign. I don’t think I’ve ever said “cite my stuff” when uncited, but sometimes a paper that cites me and follows up on something in my own work, and I step in to clarify. It would be disingenuous to hide my identity at that point.

The take home message on peer review is: The veil of anonymity in peer review unfairly confers advantages to influential researchers, but the removal of that veil creates a new set of more pernicious effects for less influential researchers.

–

Thanks to Dezene Huber whose remark prompted me to elevate this post from the queue of unwritten posts.

Maybe I am a writer after all

StandardI’ve been head down, focusing on writing grants lately. These days I spend a good deal of my time writing and thinking about writing, which isn’t what I imagined life as a scientist to be.

When I was much younger, I wanted to be a writer. I read voraciously. Mainly fantasy novels and classics like Jane Austen and Lucy Maud Montgomery. I spent a lot of time out in the fields and woods around the places we lived and in my head in worlds far from my own. Being a writer sounded so romantic. But along the way that idea faded. Writing in my English classes was uninspiring and the one thing I didn’t do was write, which is of course what makes one a writer. I continued to read with my tastes broadening (but I still enjoy a good fantasy novel when I get the chance) but honestly I didn’t write that much and most of that was because I had to.

Fast-forward to my first undergraduate research project, I was working on sex-allocation in plants. The measurements came fairly easy (besides all the time they took) but once I had a complete and analyzed dataset, then came the writing. It was my first experience writing and rewriting and rewriting something. And then there was submitting it to a journal and rewriting again. I never had worked so hard at writing something but I definitely done so since then.

As my career in science has progressed, I’ve needed to take writing seriously. As an undergrad, I really had no idea how much writing was involved in most scientific fields. Unfamiliar with such things as peer-review, I was ignorant about the process between doing research and published papers.

These days I’ve published a modest number of papers but the stories behind them have really helped me grow as a writer. There was that paper that we decided to cut a significant number of words (I can’t remember the number but maybe a quarter of the paper) to try for a journal with a strict word limit (where it was rejected from). It meant looking at every single sentence to see if every word was truly necessary. The process was kind of fun and became a little like a game or puzzle. I’m still overly wordy at times but now I’m better at slashing in the later drafts. Then there was that time our paper kept getting rejected and we realized (read: my co-author because I didn’t even want to think about it anymore) that the entire introduction needed to be reframed. So we basically tossed the intro and discussion and started again. It was painful but ultimately what needed to be done. What was there before wasn’t bad writing but was setting up expectations that weren’t fulfilled by our data.

Through all of this and especially writing here, I realised that I became a writer with out even realizing it. My science has taught me more about the craft of writing than any of the English classes I took ever did (but to be fair I stopped taking these after first year of my undergraduate degree). I’m not sure if I’ll ever tackle a fiction story, and that is ok. I turned into a different kind of writer than my childhood self imagined. And I know there is a whole other craft of understanding how to construct a story, which is very different than writing a paper or a grant proposal or a blog post. I’m not arrogant enough to think my writing is a universal skill but if I did want to write a novel I now have a better idea of what that might take (writing and rewriting and rewriting and repeat).

There are lots of scientists who also write books for more general audiences suggesting that the transition from scientist to what most would consider a writer isn’t that farfetched. This Christmas I enjoyed the writing of one of my favourite people from my graduate school days, Harry Greene. “Tracks and Shadows” is a lovely, often poetic read about life as a field biologist, snakes and much more. And I haven’t picked it up yet but another Cornellian I knew has gone on to do science television and write “Mother Nature is Trying to Kill You”. It looks fun. These examples of scientists I know writing books also speak to the possibility of writing beyond scientific papers. And as the Anne Shirley books taught me, you should write what you know.

Maybe someday I’ll decide to write a book, but for now, back to those grants.

Scientists know how to communicate with the public

StandardI bet that most of us are steady consumers of science designed for the public. Books, magazines, newspaper, museum exhibits, radio, the occasional movie. The people who bring science to the masses are “science communicators.” (The phrase “science communication” is a newish one, and arguably better than “science writing,” as a variety of media involve more than just writing.)

Nearly everything I’ve seen in science communication shares a common denominator: scientists. Science communication doesn’t amount to much without researchers. Science is a human endeavor, and it’s rarely possible to tell a compelling story without directly involving the people who did the science. As restaurant servers bring food to the table and cooks typically stay in the kitchen, science communicators bring the work of scientists to the public while scientists typically focus on publishing scientific papers.

I interact with practitioners of this craft on the uncommon occasions when my research gets notice beyond the scientific community. (My university doesn’t send out press releases when my cooler papers come out, so the communicators need to find me.)

When I listen to what science communicators have said to us scientists, there are two items that are a heavy and steady drumbeat:

-

It the duty of scientists to some of our time doing science communication, and it’s also in our interests.

-

Most scientists don’t yet know how to communicate with the public.

I’m not so sure about #1. I have decided the second one is off mark, or at least so overgeneralized that it’s either wrong or useless.

It may or may not be our duty to share science with the public. (Yes, I know the arguments, reviewed here, for example.) Regardless, the last interest group that I’d look to for impartial advice on this matter would be science communicators. This would be like learning about the need for propane grilling from a propane grilling salesperson. It would be like learning about K-12 energy education from a workshop funded by a petroleum company (sadly, this is happening this week in my city). Of course science communicators think that science communication is important!

For most scientists, the division of labor between cooks and servers is just fine. (Of course there is nothing about being a technical scientist that disqualifies someone from being an effective public communicator.) There are many important things in this world, and some of us choose other things. (This next month, for what it’s worth, I’m talking to three community organizations, volunteering for an all-day science non-fair, and writing a blog post about my lab’s latest paper.) My funding agency places science communication as one potential component of broader effects, and I’m definitely listening to them. Scientists, if we want to engage the broader public, that’s great! But it would be disingenuous to tell you that it’s your duty. We all owe many things to society, and I’m cool with it if you choose, or don’t choose, to put science communication on your plate. I’m not going to be that person who is telling you what your duties are with respect to your own career. It’s up to us to forge our own trajectories and priorities.

So we all agree that scientists that don’t spend time on science communication either are, or are not, selfish bastards.

But, is it really true that most of us scientists aren’t capable of sharing our science effectively? I call BS on this canard.

If there happens to be a stray professional science communicator reading this, I imagine that I just induced a few chuckles and a shake of the head. Let me write some more to clarify.

Most of us are wholly capable of sharing our science with the public in an understandable and even interesting fashion. However, that doesn’t mean that, when interacting with the media, that we are always willing to play along. We might not want to provide the sound bite you’re looking for. We might be resisting a brief interpretation because we don’t have enough confidence that the science would end up correct in the final product. Nearly every time some scientific finding is presented to the public, it happens along with some form of a generalization. If you’re familiar with the genre of peer reviewing, you’ll know that scientists typically disdain generalizations.

How is it that we can resist the digestion of our work for public consumption? When someone claims that one of us “doesn’t know how to communicate with the public,” I propose that this overgeneralized diagnosis can almost always be broken down into two distinct categories which might apply.

- We don’t want to discuss our science in broad terms for the public because we feel that we are unqualified for the task. While the popular image of the arrogant know-it-all scientist plays well, most of us are driven by the fact that we don’t understand enough about our fields of expertise. We are resistant to analogies or general statements of findings in lay terminology because it involves a generalization from our very specific findings that may be unwarranted. And, if it is warranted, then it falls outside our expertise to comment on such a broad topic. While our experiments were designed to advance knowledge on some general topic, we feel that it is not up to us to make the decision that our findings are informative on that general topic in a way to be digested outside the scientific community.

- We actually aren’t doing an experiment that has any general relevance to the public at large. We actually are working on minutia that will not have any broad relationship to the scientific endeavor at large. We are having trouble making a generalization about its scientific importance because it lacks a broad scientific importance.

The prescription for diagnosis #1 is for us to become more arrogant and think that we are qualified to speak with the media about broader issues in science. For us to think that, as scientists sensu lato, we are able to speak broadly about scientific issues. Just as we teach about all kinds of scientific topics in the university classroom, we can interact with the media in the same way. And this is the kind of stuff that scientists who communicate with the public do all the time. They often talk about things outside the realm of their research training and expertise and get away with it. If we’re going to be doing science communication as practicing scientists, then we need to own the fact that we can talk about a whole bunch of scientific topics even though we’re not top experts in a subfield. For example, Richard Feynman once wrote a book chapter about ants. (I thought it was horrible way to illustrate his main point about doing amateur science, actually.)

The prescription for diagnosis #2 is to be a better scientist. If you’re conducting an experiment that, at its roots, lacks a purpose that can be explained to a general audience, then what is the science really work? I can explain that I work on really obscure stuff (the community ecology of litter-dwelling ants, how odors affect nest movements of ants, and how is it that some colonies of ants control the production of different kinds of ants, and how much sunlight and leaf litter ants like, for starters). But I’m working on this obscure stuff to build to a generalized understanding of biodiversity, the role of predators in the evolution of defensive behavior, how ecology and evolution result in optimized allocation patterns, and responses to climate change. I am sometimes reluctant to claim that my results can be generalized to entire fields (I need to get more arrogant in that respect), but I recognize the fact that my work is designed to ask these broad questions. If you don’t have these broad questions in mind while running the experiment, I recommend a sabbatical and a visit to the drawing board. I don’t know how often this phenomenon happens, but I have met some scientists who, when asked for the broadest possible application of their work, can only talk about the effect on a subfield of a subfield that would only influence a few people. If a project, at its greatest success, can only influence a few other scientists in the whole world, then, well, you get the idea.

Yes, scientists are good communicators. And we know how to talk to the public. We just might not think we’re the right people for the job, or that our science isn’t built for the task.

Negotiating for a faculty position: An anecdote, and what to do

StandardThis post is about a revoked job offer at a teaching institution that was in the news, and is also about how to negotiate for a job. I’ve written about negotiation priorities before, but this missive is about how to discuss those priorities with your negotiating partner.

Part A: That rescinded offer in the news

Last week, a story of outrage made the rounds. The capsule version is this: A philosopher is offered a job at a small teaching school. She tries to negotiate for the job. She then gets immediately punished for negotiating, by having the offer rescinded.

This story first broke on a philosophy blog, then into Inside Higher Ed, and some more mainstream media, if that’s what Jezebel is. There are a variety of other posts on the topic including this, and another by Cedar Reiner.

Some have expressed massive shock and appall. However, after reading the correspondence that caused the Dean to rescind the job offer, I’m not surprised at all. After initial conversations, the candidate wrote to the Dean:

As you know, I am very enthusiastic about the possibility of coming to Nazareth. Granting some of the following provisions would make my decision easier.

1) An increase of my starting salary to $65,000, which is more in line with what assistant professors in philosophy have been getting in the last few years.

2) An official semester of maternity leave.

3) A pre-tenure sabbatical at some point during the bottom half of my tenure clock.

4) No more than three new class preps per year for the first three years.

5) A start date of academic year 2015 so I can complete my postdoc.

I know that some of these might be easier to grant than others. Let me know what you think.

Here is what the Dean thought, in her words:

Thank you for your email. The search committee discussed your provisions. They were also reviewed by the Dean and the VPAA. It was determined that on the whole these provisions indicate an interest in teaching at a research university and not at a college, like ours, that is both teaching and student centered. Thus, the institution has decided to withdraw its offer of employment to you.

Thank you very much for your interest in Nazareth College. We wish you the best in finding a suitable position.

There has been a suggestion of a gendered aspect. That viewpoint is expressed well here, among other places. (There doesn’t seem to be a pay equity problem on this campus, by the way.) I wholly get the fact that aggressive negotiation has been seen as a positive trait for men and a negative trait for women. I think it is possible that gender played a role, but in my view, the explanation offered by the Dean is the most parsimonious one. (Now, my opinion will be dismissed by some because of my privilege as a tenured white dude. Oh well.) Given the information that we’ve been provided, and interpreted in light of my experiences at a variety of teaching campuses, I find the “fit” explanation credible, even if it’s not what I would have done.

A job offer is a job offer, and once an offer is made the employer should stand behind the offer. Then again, if some highly extraordinary events unfold before an agreement is reached, the institution can rescind the job offer. In this circumstance, is the candidate’s email highly extraordinary?

Did this start at “negotiation” communicate so many horrible things about the candidate that the institution should have pulled its offer? The Dean’s answer to that question was, obviously, “Yes.”

I would have answered “no.” Many others have done the yeoman’s blog work of explaining exactly how and and why that was the wrong answer to the question. I’m more interested in attempting to crawl inside the minds of the Dean and the Department that withdrew the offer. What were they thinking?

The blog that first broke this story called these items “fairly standard ‘deal-sweeteners.’” I disagree. If I try to place myself in the shoes of the Dean and the Department, then this is how I think I might have read that request:

I am not sure if I really want this position. If you are willing to stretch your budget more than you have for any other job candidate in the history of the college, then I might decide to take the job, because accepting it is not an easy decision.

1) I realize that your initial salary offer was about what Assistant Professors make at your institution, but I want to earn 20% more, as much as your Associate Professors, because that’s what new faculty starting at research universities get.

2) I’d know that 6 months of parental leave is unofficial policy and standard practice, but I want it in writing.

3) I’d like you to hire adjuncts for an extra sabbatical before I come up for tenure. By then I’m sure I’ll need a break from teaching, even though everybody else waits until after tenure to take a sabbatical.

4) Before I take this special extra sabbatical, I want an easier teaching schedule than everybody else in my department.

5) I want to stay in my postdoc for an extra year, because I’d rather do more research somewhere else than teach for you. I realize that you advertised the position to fill teaching needs, but you can hire an adjunct.

While some of these requests are the kind that I’d expect to be fulfilled by a research institution, I’m hoping that you are able to treat me like a professor from a research institution. Now that you’ve offered me this teaching job, I want my teaching obligations to be as minimal as possible. Let me know what you think.

And the Dean did exactly that: she let her know what she thought. I’m not really joking: that’s really how I think it could be seen, inside the context of a teaching- and student-centered institution.

Here is a more unvarnished version of what I imagine the Dean was thinking:

Holy moly! Who do you think we are? Don’t you realize that we want to hire you to teach? I didn’t pull the salary out of thin air, and it was aligned with what other new Assistant Professors earn here. And if you want to teach here, why the heck do you want to stay in your postdoc which presumably pays less money? If you wanted to stay in your for 18 months earning a postdoc salary, instead of coming to teach for us at a faculty-level salary, then why would you even want this job at all? Also, didn’t you realize that we advertised for the position to start this year because we need someone to teach classes in September? If you have such crazy expectations now, then I can only imagine what a pain in the butt you might be for us after you get tenure. I think it’s best if we dodge this bullet and you can try to not teach at a different university. We’re looking for someone who’s excited about teaching our students, and not as excited about finding ways to avoid interacting with them.

The fact remains that the candidate is actually seeking a teaching-centered position. However, she definitely was requesting things that an informed candidate would only ask from a research institution. I don’t think that she necessarily erred in making oversized requests, but her oversized requests were for the wrong things. They are focused on research, and not on teaching. While it might be possible that all of those requests were designed to improve the quality of instruction and the opportunities to mentor students, it clearly didn’t read that way to the Dean. We know it didn’t read that way, because the Dean clearly wrote that she thought the candidate was focused too heavily away from teaching and students. I’m not sure if that’s true, but based on the email, that perspective makes a heckvualotta sense to me.

I’d would be more inclined to chalk the unwise requests to some very poor advice about how to negotiate. I’d would have given the candidate a call and try to figure out her reasons, and if the answers were student-centered, then I’d continue the negotiation. But I can see how a reasonable Dean, Department, and Vice President of Academic Affairs could read that email and decide that the candidate was just too risky.

New tenure-track faculty hires often evolve into permanent commitments. You need to make the most of your pick. Hiring a dud is a huge loss, and it pays to be risk averse. If someone reveals that they might be a dud during the hiring process, the wise course of action is to pick someone who shows a lower probability of being a dud. However, once an offer is made, the interview is over.

But according to Nazareth College, this candidate showed her hand as a total dud, and a massive misfit for institutional priorities. Though I wouldn’t have done it, I have a hard time faulting them for pulling the offer. If they proceeded any further, they would have taken the chance that they’d wind up with an enthusiastic researcher who would have been avoiding students at every opportunity. Someone who might want to bail as soon as starting. Or maybe someone who got a better job while on the postdoc and not show up the next year. The department only has four tenure-track faculty, and would probably like to see as many courses taught by tenure-line faculty as possible.

Having worked in a few small ponds like Nazareth, I don’t see the outrageousness of these events. We really have no idea, though, because there is a lot of missing context. But we know that the Dean ran this set of pie-in-the-sky requests by the Department and her boss. They talked about it and made sure that they weren’t going to get into (legal) hot water and also made sure that they actually wanted to dump this candidate. It’s a good bet that the Department got this email and said, “Pull up, pull up! Abort!” They may have thought, “If we actually are lucky enough to fill another tenure-track line, we don’t want to waste it on someone who only wants to teach three preps before taking a pre-tenure sabbatical while we cover their courses.” I don’t know what they were thinking, of course, but this seems possible.

Karen Kelsky pointed out that offers are rescinded more often at “less prestigious institutions.” She’s definitely on to something. Less prestigious institutions have more weighty teaching loads and fewer resources for research (regardless of the cost of tuition). These are the kinds of institutions that are most likely to find faculty job candidates who are wholly unprepared for the realities of life on the job.

When an offer gets pulled, I imagine it’s because the institution sees that they’ve got a pezzonovante on their hands and they get out while they still can.

At teaching institutions, nobody wants a faculty member who shies away from the primary job responsibility: teaching.

In a research institution, how would the Dean and the Department feel if a job candidate asked the Dean for reduced research productivity expectations and a higher teaching load for the first few years? Wouldn’t that freak the Department out and show that they didn’t get a person passionate for research? Wouldn’t the Dean rethink that job offer? Why should it be any different for someone wanting to duck teaching at a teaching institution?

I don’t know what happened on the job interview, but that email from the candidate to the Dean is a huge red flag word embroidered with script that reads: “I don’t want to teach” and “I expect you to give me resources just like a research university would.” Of course everybody benefits when new faculty members get reassigned time to stabilize. But these requests were not just over the top, they were in orbit.

If I were the Dean at a teaching campus, what kinds of things would I want to see from my humanities job candidates? How about a guarantee for the chance to teach a specialty course? Funds to attend special conferences and funds to hire students as research assistants. Someone wanting to start early so that they could start curriculum development. Someone wanting a summer stipend to do research outside the academic year?

Here’s the other big problem I have with the narrative that has dogpaddled around this story. It’s claimed that the job offer was rescinded because she wanted to negotiate. But that’s not the case. The job candidate was not even negotiating.

Part B: What exactly is negotiation and how do you do it with a teaching institution?

A negotiation is a discussion of give and take. You do this for me, I do this for you. You give me the whip, and I’ll throw you the idol.

In the pulled offer at Nazareth College, the job candidate was attempting to “negotiate” like Satipo (the dude with the whip), but from other side of the gap.

What the Dean received from the candidate wasn’t even a start to a negotiation. It was, “Here is everything I want from you, how much can you give to me?” That is not a negotiation. A negotiation says, “Here are some things I’m interested in from you. If you give me these things, this is what I have to offer.”

How should this candidate have started the negotiation? Well, actually, the email should have been a request to schedule a phone conversation. What should the content of that conversation have been? How could the candidate have broached the huge requests (pre-tenure sabbatical, starting in 18 months, very few preps, huge salary)? By acknowledging that by providing these huge requests, huge output would come back.

“Once I get a contract for my second book, could you give me a pre-tenure sabbatical to write this book?”

“I’m concerned I won’t be able balance my schedule if I have too many preps early on. If you can keep my preps down to three per year, I’ll be more confident in my teaching quality and I should be able to continue writing manuscripts at the same time.”

“Right now, I am working on this exciting project during my postdoc, which is funded for another year. If it’s possible for me to arrive on campus after I finish my postdoc, this work will really help me create an innovative curriculum for [a course I will be teaching]. During this postdoc, I’d be glad to host some students from the college for internships and help them build career connections.” Of course, it’s very rare a teaching institution wants to wait a whole extra year. They want someone to teach, after all! It couldn’t hurt much to ask, if you phrase it like this, verbally.

“After running the numbers, I see that a salary of $65,000 is standard on the market for new faculty at sister institutions. But from what I’ve seen from the salary survey, this is well above the median salary for incoming faculty. If you can find the funds to bring me in at this salary, I’m okay if you trim back moving expenses. Being paid at current market rate in my field is important to me, and if you let me know what level of performance is tied to that level of compensation, I’ll deliver.”

By no means am I a negotiation pro. What I do know comes mostly from the classic book, “Getting to Yes.” The main point of this book is that “positional negotiation” is less likely to be successful. This approach involves opposite sides taking extreme positions and then finding a middle ground. Just like asking for a huge salary, and lots of reassigned time and easy teaching.

Getting to Yes explains how to do “principled negotiation.” In this case, you have a true negotiating partner in which you understand and respect one another’s interests. So, instead of haggling over salary like buying a used piece of furniture at a swap meet, you discuss the basis for the salary and what each of you will get out of it.

If you are asking for a reduced teaching load, then you explain what you will deliver with this reduced teaching load (higher quality teaching and more scholarship), and what the consequences will be if you don’t get it (potential struggle while teaching and fear that you won’t have time to do scholarship). And so on. The quotes I suggested above are what you’d expect to see in a principled negotiation. The book is a bit long but there are some critical ideas in there, and I’m really glad I read it before I negotiated my current position. When it was done, both I and the Dean thought we won, and we reached a fair agreement.

If you are in the position of receiving an academic job offer, negotiating for the best starting position is critical. You don’t have to be afraid of having the offer withdrawn as long as you’re negotiating in good faith. That mean you communicate an understanding the constraints and interests of your negotiating partner. And being sure that when you are ask for something, your reason is designed to fulfill the interests of your partner as much as yourself. So, asking for a bunch of different ways to get out of teaching responsibilities is a non-starter when your main job responsibility is teaching.

It’s not only acceptable to negotiate when you are starting an academic job, it’s expected. The worst lesson to take from this incident is Nazareth is that there is peril in negotiation. I suggest that the lesson is that you must negotiate. And, keep in mind that negotiation is a conversation and a partnership towards a common goal. Even when it comes to money, there is a common goal: You want to be paid enough that you’ll be happy and stay, and they want you to be paid enough that you’ll stay.

You won’t have anybody pull a job offer from you if you’re genuinely negotiating. It’s okay to ask for things that your negotiating partner can’t, or may not want to, deliver. However, what you ask for should reflect what you really truly want, and at the moment you’re asking, provide a clear rationale, so that you appear reasonable. If you’re interviewing for jobs, then I recommend picking up a copy of Getting to Yes.

I own my data, until I don’t.

StandardScience is in the middle of a range war, or perhaps a skirmish.

Ten years ago, I saw a mighty good western called Open Range. Based on the ads, I thought it was just another Kevin Costner vehicle. But Duncan Shepherd, the notoriously stingy movie critic, gave it three stars. I not only went, but also talked my spouse into joining me. (Though she needs to take my word for it, because she doesn’t recall the event whatsoever.)

The central conflict in Open Range is between fatcat establishment cattle ranchers and a band of noble itinerant free grazers. The free grazers roam the countryside with their cows in tow, chewing up the prairie wherever they choose to meander. In the time the movie was set, the free grazers were approaching extirpation as the western US was becoming more and more subdivided into fenced parcels. (That’s why they filmed it in Alberta.) To learn more about this, you could swing by the Barbed Wire Museum.

The ranchers didn’t take kindly to the free grazers using their land. The free grazers thought, well, that free grazing has been a well-established practice and that grass out in the open should be free.

If you’ve ever passed through the middle of the United States, you’d quickly realize that the free grazers lost the range wars.

On the prairie, what constitutes community property? If you’re on loosely regulated public land administered by the Bureau of Land Management, then you can use that land as you wish, but for certain uses (such as grazing), you need to lease it from the government. You can’t feed your cow for free, nowadays. That community property argument was settled long ago.

Now to the contemporary range wars in science: What constitutes community property in the scientific endeavor?

In recent years, technological tools have evolved such that scientists can readily share raw datasets with anybody who has an internet connection. There are some who argue that all raw data used to construct a scientific paper should become community property. Some have the extreme position that as soon as a datum is collected, regardless of the circumstances, it should become public knowledge as promptly as it is recorded. At the other extreme, some others think that data are the property of the scientists who created them, and that the publication of a scientific paper doesn’t necessarily require dissemination of raw data.

Like in most matters, the opinions of most scientists probably lie somewhere between the two poles.

The status quo, for the moment, is that most scientists do not openly disseminate their raw data. In my field, most new papers that I encounter are not accompanied with fully downloadable raw datasets. However, some funding agencies are requiring the availability of raw data. There are a few journals of which I am aware that require all authors to archive data upon publication, and there are many that support but do not require archiving.

The access to other people’s data, without the need to interact with the creators of the data, is increasing in prevalence. As the situation evolves, folks on both sides are getting upset at the rate of change – either it’s too slow, or too quick, or in the wrong direction.

Regardless of the trajectory of “open science,” the fact remains that, at the moment, we are conducing research in a culture of data ownership. With some notable exceptions, the default expectation is that when data are collected, the scientist is not necessarily obligated to make these data available to others.

Even after a paper is published, there is no broadly accepted community standard that the data that resulted in the paper become public information. On what grounds do I assert this? Well, last year I had three papers come out, all of which are in reputable journals (Biotropica, Naturwissenschaften, and Oikos, if you’re curious). In the process of publishing these papers, nobody ever even hinted that I could or should share the data that I used to write these papers. This is pretty good evidence that publishing data is not yet standard practice, though things are slowly moving in that direction. As evidence, I just got an email from Oikos as a recent author asking me to fill out a survey to let them know how I feel about data archiving policies for the journal.

As far as the world is concerned, I still own the data from those three papers published last year. If you ask me for the data, I’d be glad to share them with you after a bit of conversation, but for the moment, for most journals it seems to be my choice. I don’t think any of those three journals have a policy indicating that I need to share my dataset with the public. I imagine this could change in the near future.

I was chatting with a collaborator a couple weeks ago (working on “paper i”) and we were trying to decide where we should send the paper. We talked about PLOS ONE. I’ve sent one paper to this journal, actually one of best papers. Then I heard about a new policy of the journal to require public archiving of datasets from all papers published in the journal.

All of sudden, I’m less excited about submitting to this journal. I’m not the only one to feel this way, you know.

Why am I sour on required data archiving? Well, for starters, it is more work for me. We did the field and lab work for this paper during 2007-2009. This is a side project for everybody involved and it’s taken a long time to get the activation energy to get this paper written, even if the results are super-cool.

Is that my fault that it’ll take more work to share the data? Sure, it’s my fault. I could have put more effort into data management from out outset. But I didn’t, as it would have been more effort, and kept me from doing as much science as I have done. It comes with temporal overhead. Much of the data were generated by an undergraduate researcher, a solid scientist with decent data management practices. But I was working with multiple undergraduates in the field in that period of time, and we were getting a lot done. I have no doubts in the validity of the science we are writing up, but I am entirely unthrilled about cleaning up the dataset and adding the details into the metadata for the uninitiated. And, our data are a combination of behavioral bioassays, GC-MS results from a collaborator, all kinds of ecological field measurements, weather over a period of months, and so on. To get these numbers into a downloadable and understandable condition would be, frankly, an annoying pain in the ass. And anybody working on these questions wouldn’t want the raw data anyway, and there’s no way these particular data would be useful in anybody’s meta analysis. It’d be a huge waste of my time.

Considering the time it takes me to get papers written, I think it’s cute that some people promoting data archiving have suggested a 1-year embargo after publication. (I realize that this is a standard timeframe for GenBank embargoes.) The implication is that within that one year, I should be able to use that dataset for all it’s worth before I share it with others. We may very well want to use these data to build a new project, and if I do, then it probably would be at least a year before we head back to the rainforest again to get that project done. At least with the pace of work in my lab, an embargo for less than five years would be useless to me.

Sometimes, I have more than one paper in mind when I am running a particular experiment. More often, when writing a paper, I discover the need to write different one involving the same dataset (Shhh. Don’t tell Jeremy Fox that I do this.) I research in a teaching institution, and things often happen at a slower pace than at the research institutions which are home to most “open science” advocates. Believe it or not, there are some key results from a 15-year old dataset that I am planning to write up in the next few years, whenever I have the chance to take a sabbatical. This dataset has already been featured in some other papers.

One of the standard arguments for publishing raw datasets is that the lack of full data sharing slows down the progress of science. It is true that, in the short term, more and better papers might be published if all datasets were freely downloadable. However, in the long term, would everybody be generating as much data as they are now? Speaking only for myself, if I realized that publishing a paper would require the sharing of all of the raw data that went into that paper, then I would be reluctant to collect large and high-risk datasets, because I wouldn’t be sure to get as large a payoff from that dataset once the data are accessible.

Science is hard. Doing science inside a teaching institution is even harder. I am prone isolation from the research community because of where I work. By making my data available to others online without any communication, what would be the effect of sharing all of my raw data? I could either become more integrated with my peers, or more isolated from them. If I knew that making my data freely downloadable would increase interactions with others, I’d do it in a heartbeat. But when my papers get downloaded and cited I’m usually oblivious to this fact until the paper comes out. I can only imagine that the same thing could happen with raw data, though the rates of download would be lower.

In the prevailing culture, when data are shared, along with some other substantial contributions, that’s standard grounds for authorship. While most guidelines indicate that providing data to a collaborator is not supposed to be grounds for authorship, the current practice is that it is grounds for authorship. One can argue that it isn’t fair nor is it right, but that is what happens. Plenty of journals require specification of individual author contributions and require that all authors had a substantial role beyond data contribution. However, this does not preclude that the people who provide data do not become authors.

In the culture of data ownership, the people who want to write papers using data in the hands of other scientists need to come to an agreement to gain access to these data. That agreement usually involves authorship. Researchers who create interesting and useful data – and data that are difficult to collect – can use those data as a bargaining chip for authorship. This might not be proper or right, and this might not fit the guidelines that are published by journals, but this is actually what happens.

This system is the one that “open science” advocates want to change. There are some databases with massive amounts of ecological and genomic data that other people can use, and some people can go a long time without collecting their own data and just use the data of others. I’m fine with that. I’m also fine with not throwing my data in to the mix.

My data are hard-won, and the manuscripts are harder-won. I want to be sure that I have the fullest opportunity to use my data before anybody else has the opportunity. In today’s marketplace of science, having a dataset cited in a publication isn’t much credit at all. Not in the eyes of search committees, or my Dean, or the bulk of the research community. The discussion about the publication of raw data often avoids tacit facts about authorship and the culture of data ownership.

To be able to collect data and do science, I need grant money.

To get grant money, I need to give the appearance of scientific productivity.

To show scientific productivity, I need to publish a bunch of papers.

To publish a bunch of papers, I need to leverage my expertise to build collaborations.

To leverage my expertise to build collaborations, I need to have something of quality to offer.

To have something of quality to offer, I need to control access to the data that I have collected. I don’t want that to stop after publication.

The above model of scientific productivity is part of the culture of data ownership, in which I have developed my career at a teaching institution. I’m used to working amicably and collaboratively, and the level of territoriality in my subfields is quite low. I’ve read the arguments, but I don’t see how providing my data with no strings attached would somehow build more collaborations for me, and I don’t see how it would give me any assistance in the currency that matters. I am sure that “open science” advocates are wholly convinced that putting my data online would increase, rather than constrict opportunities for me. I am not convinced, yet, though I’m open to being convinced. I think what will convince me is seeing a change in the prevailing culture.

There is one absurdity to these concerns of mine, that I’m sure critics will have fun highlighting. I doubt many people would be downloading my data en masse. But, it’s not that outlandish, and people have done papers following up on my own work after communicating with me. I work at a field site where many other people work; a new paper comes out from this place every few days. I already am pooling data with others for collaborations. I’d like to think that people want to work with me because of what I can bring to the table other than my data, but I’m not keen on testing that working hypothesis.

Simply put, in today’s scientific rewards system, data are a currency. Advocates of sharing raw data may argue that public archiving is like an investment with this currency that will yield greater interest than a private investment. The factors that shape whether the yield is greater in a public or private investment of the currency of data are complicated. It would be overly simplistic to assert that I have nothing to lose and everything to gain by sharing my raw data without any strings attached.

While good things come to those who are generous, I also have relatively little to give, and I might not be doing myself or science a service if I go bankrupt. Anybody who has worked with me will report (I hope) that am inclusive and giving with what I have to offer. I’ve often emailed datasets without people even asking for them, without any restrictions or provisions. I want my data to be used widely. But even more, I want to be involved when that happens.

Because I run a small operation in a teaching institution, my research program experiences a set of structural disadvantages compared to colleagues at an R1 institution. The requirement to share data levies the disadvantage disproportionately against researchers like myself, and others with little funding to rapidly capitalize on the creation of quality data.

To grow a scientific paper, many ingredients are required. As grass grows the cow, data grows a scientific paper.

In Open Range, the resource in dispute is not the grass, but the cows. The bad guy ranchers aren’t upset about losing the grass, they just don’t want these interlopers on their land. It’s a matter of control and territoriality. At the moment, the status quo is that we run our own labs, and the data growing in these labs are also our property.

When people don’t want to release their data, they don’t care about the data itself. They care about the papers that could result from these data. I don’t care if people have numbers that I collect. What I care about is the notion that these numbers are scientifically useful, and that I wish to get scientific credit for the usefulness of these numbers. Once the data are public, there is scant credit for that work.

It takes plenty of time and effort to generate data. In my case, lots of sweat, and occasionally some venom and blood, is required to generate data. I also spend several weeks per year away from my family, which any parent should relate with. Many of the students who work with me also have made tremendous personal investments into the work as well. Generating data in my lab often comes at great personal expense. Right now, if we publicly archived data that were used in the creation of a new paper, we would not get appropriate credit in a currency of value in the academic marketplace.

When a pharmaceutical company develops a new drug, the structure of the drug is published. But the company has a twenty year patent and five years of exclusivity. It’s widely claimed – and believed – that without the potential for recouping the costs of work in developing medicines that pharmaceutical companies wouldn’t jump through all the regulatory hoops to get new drugs on the market. The patent provides incentive for drug production. Some organizations might make drugs out of the goodness of their hearts, but the free market is driven by dollars. An equivalent argument could be wagered for scientists wishing for a very long time window to reap the rewards of producing their own data.

In the United States, most meat that people consume doesn’t come from grass on the prairie, but from corn grown in an industrial agricultural setting. Likewise, most scientific papers that get published come from corn-fed data produced by a laboratory machine designed to crank out a high output of papers. Ranchers stay in business by producing a lot of corn, and maximizing the amount of cow tissue that can be grown with that corn. Scientists stay in business by cranking out lots of data and maximizing how many papers can be generated from those data.

Doing research in a small pond, my laboratory is ill equipped to compete with the massive corn-fed laboratories producing many heads of cattle. Last year was a good year for me, and I had three papers. That’s never going to be able to compete with labs at research institutions — including the ones advocating for strings-free access to everybody’s data.

The movement towards public data archiving is essentially pushing for the deprivatization of information. It’s the conversion of a private resource into a community resource. I’m not saying this is bad, but I am pointing out this is a big change. The change is biggest for small labs, in which each datum takes a relatively greater effort to produce, and even more effort to bring to publication.

So far, what I’ve written is predicated on the notion that researchers (or their employers) actually have ownership of the data that they create. So, who actually owns data? The answer to that question isn’t simple. It depends on who collected it, who funded the collection of the data, and where the data were published.

If I collect data on my own dime, then I own these data. If my data were collected under the funding support of an agency (or a branch of an agency) that doesn’t require the public sharing of the raw data, then I still own these data. If my data are published in a journal that doesn’t require the publication of raw data, I still own these data.

It’s fully within the charge of NIH, NSF, DOE, USDA, EPA and everyone else to require the open sharing of data collected under their support. However, federal funding doesn’t necessarily necessitate public ownership (see this comment in Erin McKiernan’s blog for more on that.) If my funding agency, or some federal regulation, requires that my raw data be available for free downloads, then I no longer own these data. The same is true if a journal has a similar requirement. Also, if I choose to give away my data, then I no longer own them.

So, who is in a position to tell me when I need to make my data public? My program officer, or my editor.

If you wish, you can make it your business by lobbying the editors of journals to change their practices, and you can lobby your lawmakers and federal agencies for them to require and enforce the publication of raw datasets.

I think it’s great when people choose to share data. I won’t argue with the community-level benefits, though the magnitude of these benefits to the community vary with the type of data. In my particular situation, when I weigh the scant benefit to the community relative to the greater cost (and potential losses) to my research program, the decision to stay the course is mighty sensible.

There are some well-reasoned folks, who want to increase the publication of raw datasets, who understand my concerns. If you don’t think you understand my concerns, you really need to read this paper. In this paper, they had four recommendations for the scientific community at large, all of which I love:

Facilitate more flexible embargoes on archived data

Encourage communication between data generators and re-users

Disclose data re-use ethics

Encourage increased recognition of publicly archived data.

(It’s funny, in this paper they refer to the publication of raw data as “PDA” (public data archiving), but at least here in the States, that acronym means something else.)

And they’re right, those things will need to happen before I consider publishing raw data voluntarily. Those are the exact items that I brought up as my own concerns in this post. The embargo period would need to be far longer, and I’d want some reassurance that the people using my data will actually contact me about it, and if it gets re-used, that I have a genuine opportunity for collaboration as long as my data are a big enough piece. And, of course, if I don’t collaborate, then the form of credit in the scientific community will need to be greater than what happens now, which is getting just cited.

The Open Data Institute says that “If you are publishing open data, you are usually doing so because you want people to reuse it.” And I’d love for that to happen. But I wouldn’t want it to happen without me, because in my particular niche in the research community, the chance to work with other scientists is particularly valuable. I’d prefer that my data to be reused less often than more often, as long as that restriction enabled me more chances to work directly with others.

Scientists at teaching institutions have a hard time earning respect as researchers (see this post and read the comments for more on that topic). By sharing my data, I realize that I can engender more respect. But I also open myself up to being used. When my data are important to others, then my colleagues contact me. If anybody feels that contacting me isn’t necessary, then my data are not apparently necessary.

Is public data archiving here to stay, or is it a passing fad? That is not entirely clear.

There is a vocal minority that has done a lot to promote the free flow of raw data, but most practicing scientists are not on board this train. I would guess that the movement will grow into an establishment practice, but science is an odd mix of the revolutionary and the conservative. Since public data archiving is a practice that takes extra time and effort, and publishing already takes a lot work, the only way will catch on is if it is required. If a particular journal or agency wants me to share my data, then I will do so. But I’m not, yet, convinced that it is in my interest.

I hope that, in the future, I’ll be able to write a post in which I’m explaining why it’s in my interest to publish my raw data.

The day may come when I provide all of my data for free downloads, but that day is not today.

I am not picking up a gun in this range war. I’ll just keep grazing my little herd of cows in a large fragment of rainforest in Sarapiquí, Costa Rica until this war gets settled. In the meantime, if you have a project in mind involving some work I’ve done, please drop me a line. I’m always looking for engaged collaborators.

Avoiding bad teaching evaluations: Tricks of the trade

StandardStudent evaluations are the main method used to evaluate our teaching. These evaluations are, at best, an imperfect measuring tool.

Lots of irrelevant stuff affects evaluation scores. If you’re attractive or well dressed, this helps your scores. If you are a younger woman, you have to reckon with a distinct set of challenges and biases. If the weather is better out, you might get better evaluations, too. So, don’t feel bad about doing things to help your scores, even if they aren’t connected to teaching quality.

My university aptly calls these forms by their acronym, “PTE”: Perceived Teaching Effectiveness. Note the word: “perceived.” Actual effectiveness is moot.