Instead of writing about the publication cycle in the abstract, I thought it might be more illustrative to explain what is in each category at this moment. (It might be perplexing, annoying or overbearing, too. I guess I’m taking that chance.) My list is just that – a list. Here, I amplify to describe how the project was placed on the treadmill and how it’s moving along, or not moving along. I won’t bore those of you with the details of ecology, myrmecology or tropical biology, and I’m not naming names. But you can get the gist.

Any “Student” is my own student – and a “Collaborator” is anybody outside my own institution with whom I’m working, including grad students in other labs. A legend to the characters is at the end.

Manuscript completed

Paper A: Just deleted from this list right now! Accepted a week ago, the page proofs just arrived today! The idea for this project started as the result of a cool and unexpected natural history observation by Student A in 2011. Collaborator A joined in with Student B to do the work on this project later that summer. I and Collab A worked on the manuscript by email, and I once took a couple days to visit Collab A at her university in late 2011 to work together on some manuscripts. After that, it was in Collab A’s hands as first author and she did a rockin’ job (DOI:10.1007/s00114-013-1109-3).

Paper B: I was brought in to work with Collab B and Collab C on a part of this smallish-scale project using my expertise on ants. I conducted this work with Student C in my lab last year and the paper is now in review in a specialized regional journal (I think).

Paper C: This manuscript is finished but not-yet-submitted work by a student of Collab D, which I joined in by doing the ant piece of the project. This manuscript requires some editing, and I owe the other authors my remarks on it. I realize that I promised remarks about three months ago, and it would take only an hour or two, so I should definitely do my part! However, based on my conversations, I’m pretty sure that I’m not holding anything up, and I’m sure they’d let me know if I was. I sure hope so, at least.

Paper D: The main paper out of Student A’s MS thesis in my lab. This paper was built with from Collab E and Collab F and Student D. Student A wrote the paper, I did some fine-tuning, and it’s been on a couple rounds of rejections already. I need to turn it around again, when I have the opportunity. There isn’t anything in the reviews that actually require a change, so I just need to get this done.

Paper E: Collab A mentored Student H in a field project in 2011 at my field site, on a project that was mostly my idea but refined by Collab A and Student H. The project worked out really well, and I worked on this manuscript the same time as Paper A. I can’t remember if it’s been rejected once or not yet submitted, but either way it’s going out soon. I imagine it’ll come to press sometime in the next year.

Manuscripts in Progress

Paper F: Student D conducted the fieldwork in the summer of 2012 on this project, which grew out of a project by student A. The data are complete, and the specific approach to writing the paper has been cooked up with Student D and myself, and now I need to do the full analysis/figures for the manuscript before turning it off to StudentD to finish. She is going away for another extended field season in a couple months, and so I don’t know if I’ll get to it by then. If I do, then we should submit the paper in months. If I don’t, it’ll be by the end of 2014, which is when Student D is applying to grad schools.

Paper G: Student B conducted fieldwork in the summer of 2012 on a project connected to a field experiment set up by Collab C. I spent the spring of 2013 in the lab finishing up the work, and I gave a talk on it this last summer. It’s a really cool set of data though I haven’t had the chance to work it up completely. I contacted Collab G to see if he had someone in his lab that wanted to join me in working on it. Instead, he volunteered himself and we suckered our pal Collab H to join us in on it. The analyses and writing should be straightforward, but we actually need to do it and we’re all committed to other things at the moment. So, now I just need to make the dropbox folder to share the files with those guys and we can take the next step. I imagine it’ll be done somewhere between months to years from now, depending on how much any one of us pushes.

Paper H: So far, this one has been just me. It was built on a set of data that my lab has accumulated over few projects and several years. It’s a unique set of data to ask a long-standing question that others haven’t had the data to approach. The results are cool, and I’m mostly done with them, and the manuscript just needs a couple more analyses to finish up the paper. I, however, have continued to be remiss in my training in newly emerged statistical software. So this manuscript is either waiting for myself to learn the software, or for a collaborator or student eager to take this on and finish up the manuscript. It could be somewhere between weeks to several years from now.

Paper I: I saw a very cool talk by someone a meeting in 2007, which was ripe to be continued into a more complete project, even though it was just a side project. After some conversations, this project evolved into a collaboration, with Student E to do fieldwork in summer 2008 and January 2009. We agreed that Collab I would be first author, Student E would be second author and I’d be last author. The project is now ABM (all but manuscript), and after communicating many times with Collab I over the years, I’m still waiting for the manuscript. A few times I indicated that I would be interested in writing up our half on our own for a lower-tier journal. It’s pretty much fallen off my radar and I don’t see when I’ll have time to write it up. Whenever I see my collaborator he admits to it as a source of guilt and I offer absolution. It remains an interesting and timely would-be paper and hopefully he’ll find the time to get to it. However, being good is better than being right, and I don’t want to hound Collab I because he’s got a lot to do and neither one of us really needs the paper. It is very cool, though, in my opinion, and it’d be nice for this 5-year old project to be shared with the world before it rots on our hard drives. He’s a rocking scholar with a string of great papers, but still, he’s in a position to benefit from being first author way more myself, so I’ll let this one sit on his tray for a while longer. This is a cool enough little story, though, that I’m not going to forget about it and the main findings will not be scooped, nor grow stale, with time.

Paper J: This is a review and meta-analysis that I have been wanting to write for a few years now, which I was going to put into a previous review, but it really will end up standing on its own. I am working with a Student F to aggregate information from a disparate literature. If the student is successful, which I think is likely, then we’ll probably be writing this paper together over the next year, even as she is away doing long-term field research in a distant land.

Paper K: At a conference in 2009, I saw a grad student present a poster with a really cool result and an interesting dataset that came from the same field station as myself. This project was built on an intensively collected set of samples from the field, and those same samples, if processed for a new kind of lab analysis, would be able to test a new question. I sent Student G across the country to the lab of this grad student (Collab J) to process these samples for analysis. We ran the results, and they were cool. To make these results more relevant, the manuscript requires a comprehensive tally of related studies. We decided that this is the task of Student G. She has gotten the bulk of it done over the course of the past year, and should be finishing in the next month or two, and then we can finish writing our share of this manuscript. Collab J has followed through on her end, but, as it’s a side project for both of us, neither of us are in a rush and the ball’s in my court at the moment. I anticipate that we’ll get done with this in a year or two, because I’ll have to analyze the results from Student G and put them into the manuscript, which will be first authored by Collab J.

Paper L: This is a project by Student I, as a follow-up to the project of Student H in paper E, conducted in the summer of 2013. The data are all collected, and a preliminary analysis has been done, and I’m waiting for Student I to turn these data into both a thesis and a manuscript.

Paper M: This is a project by Student L, building on prior projects that I conducted on my own. Fieldwork was conducted in the summer of 2012, and it is in the same place as Paper K, waiting for the student to convert it into a thesis and a manuscript.

Paper N: This was conducted in the field in summer 2013 as a collaboration between Student D and Student N. The field component was successful and now requires me to do about a month’s worth of labwork to finish up the project, as the nature of the work makes it somewhere between impractical and unfeasible to train the students to do themselves. I was hoping to do it this fall, to use these data not just for a paper but also preliminary data for a grant proposal in January, but I don’t think I’ll be able to do it until the spring 2014, which would mean the paper would get submitted in Fall 2014 at the earliest, or maybe 2015. This one will be on the frontburner because Students D and N should end up in awesome labs for grad school and having this paper in press should enhance their applications.

Paper O: This project was conducted in the field in summer 2013, and the labwork is now in the hands of Student O, who is doing it independently, as he is based out of an institution far away from my own and he has the skill set to do this. I need to continue communicating with this student to make sure that it doesn’t fall off the radar or doesn’t get done right.

Paper P: This project is waiting to get published from an older collaborative project, a large multi-PI biocomplexity endeavor at my fieldstation. I had a postdoc for one year on this project, and she published one paper from the project but as she moved on, left behind a number of cool results that I need to write up myself. I’ve been putting this off because it would rely on me also spending some serious lab time doing a lot of specimen identifications to get this integrative project done right. I’ve been putting it off for a few years, and I don’t see that changing, unless I am on a roll from the work for Paper N and just keep moving on in the lab.

Paper Q: A review and meta-analysis that came out of a conversation with Collabs K and L. I have been co-teaching field courses with Collab K a few times, and we share a lot of viewpoints about this topic that go against the incorrect prevailing wisdom, so we thought we’d do something about it. This emerged in the context of a discussion with L. I am now working with Student P to help systematically collect data for this project, which I imagine will come together over the next year or two, depending on how hard the pushing comes from myself or K or L. Again it’s a side project for all of us, so we’ll see. The worst case scenario is that we’ll all see one another again next summer and presumably pick things up from there. Having my student generating data is might keep the engine running.

Paper R: This is something I haven’t thought about in a year or so. Student A, in the course of her project, was able to collect samples and data in a structured fashion that could be used with the tools developed by Collab M and a student working with her. This project is in their hands, as well as first and lead authorship, so we’ve done our share and are just waiting to hear back. There have been some practical problem on their side, that we can’t control, and they’re working to get around it.

Paper S: While I was working with Collab N on an earlier paper in the field in 2008, a very cool natural history observation was made that could result in an even cooler scientific finding. I’ve brought in Collab O to do this part of the work, but because of some practical problems (the same as in Paper R, by pure coincidence) this is taking longer than we thought and is best fixed by bringing in the involvement of a new potential collaborator who has control over a unique required resource. I’ve been lagging on the communication required for this part of the project. After I do the proper consultation, if it works out, we can get rolling and, if it works, I’d drop everything to write it up because it would be the most awesome thing ever. But, there’s plenty to be done between now and then.

Paper T: This is a project by Student M, who is conducted a local research project on a system entirely unrelated to my own, enrolled in a degree program outside my department though I am serving as her advisor. The field and labwork was conducted in the first half of 2013 – and the potential long-shot result come up positive and really interesting! This one is, also, waiting for the student to convert the work into a thesis and manuscript. You might want to note, by the way, that I tell every Master’s student coming into my lab that I won’t sign off on their thesis until they also produce a manuscript in submittable condition.

Projects in development

These are still in the works, and are so primordial there’s little to say. A bunch of this stuff will happen in summer 2014, but a lot of it won’t, even though all of it is exciting.

Summary

I have a lot of irons in the fire, though that’s not going to keep me from collecting new data and working on new ideas. This backlog is growing to an unsustainable size, and I imagine a genuine sabbatical might help me lighten the load. I’m eligible for a sabbatical but I can’t see taking it without putting a few projects on hold that would really deny opportunities to a bunch of students. Could I have promoted one of these manuscripts from one list to the other instead of writing this post? I don’t think so, but I could have at least made a small dent.

Legend to Students and Collaborators

Student A: Former M.S. student, now entering her 2nd year training to become a D.P.T.; actively and reliably working on the manuscript to make sure it gets published

Student B: Former undergrad, now in his first year in mighty great lab and program for his Ph.D. in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

Student C: Former undergrad, now in a M.S. program studying disease ecology from a public health standpoint, I think.

Student D: Undergrad still active in my lab

Student E: Former undergrad, now working in biology somewhere

Student F: Former undergrad, working in my lab, applying to grad school for animal behavior

Student G: Former undergrad, oriented towards grad school, wavering between something microbial genetics and microbial ecology/evolution (The only distinction is what kind of department to end up in for grad school.)

Student H: Former undergrad, now in a great M.S. program in marine science

Student I: Current M.S. student

Student L: Current M.S. student

Student M: Current M.S. student

Student N: Current undergrad, applying to Ph.D. programs to study community ecology

Student O: Just starting undergrad at a university on the other side of the country

Student P: Current M.S. student

Collab A: Started collaborating as grad student, now a postdoc in the lab of a friend/colleague

Collab B: Grad student in the lab of Collab C

Collab C: Faculty at R1 university

Collab D: Faculty at a small liberal arts college

Collab E: Faculty at a small liberal arts college

Collab F: International collaborator

Collab G: Faculty at an R1 university

Collab H: Started collaborating as postdoc, now faculty at an R1 university

Collab I: Was Ph.D. student, now faculty at a research institution

Collab J: Ph.D. student at R1 university

Collab K: Postdoc at R1 university, same institution as Collab L

Collab L: Ph.D. student who had the same doctoral PI as Collab A

Collab M: Postdoc at research institution

Collab N: Former Ph.D. student of Collab H.; postdoc at research institution

Collab O: Faculty at a teaching-centered institution similar to my own

By the way, if you’re still interested in this topic, there was also a high-quality post on the same topic on Tenure, She Wrote, using a fruit-related metaphor with some really nice fruit-related photos.

I couple years ago, there was a careers-in-science discussion on an

I couple years ago, there was a careers-in-science discussion on an

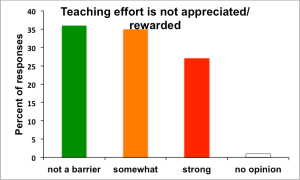

Class needs to end when it is supposed to end.

Class needs to end when it is supposed to end.