This post grows out of a conversation I was having about how scientists purchase supplies and equipment at smaller institutions. It would be helpful if you could leave comments with information and experiences you have. Continue reading

R1 vs non-R1

How can track record matter in double-blind grant reviews?

StandardWe should have double blind grant reviews. I made this argument a couple weeks ago, which was met with general agreement. Except for one thing, which I now address.

Some readers said that double-blind reviews can’t work, or are inadvisable, because of the need to evaluate the PI’s track record. I disagree with my whole heart. I think we can make it work. If our community is going to make progress on diversity and equity like we keep trying to do, then we have to make it work.

Some readers said that double-blind reviews can’t work, or are inadvisable, because of the need to evaluate the PI’s track record. I disagree with my whole heart. I think we can make it work. If our community is going to make progress on diversity and equity like we keep trying to do, then we have to make it work.

We can’t just put up our hands and say, “We need to keep it the same because the alternative won’t work” because the status quo is clearly biased in a way that continues to damage our community. Continue reading

The lost opportunity cost of overcommitment

StandardMy sabbatical officially started a few days ago. I was half-expecting a kind of weight to lift. But my brain isn’t letting me have any of that.

For the last year or so, I’ve been stockpiling things “for sabbatical.” Now, I’m looking at the weight of that list. Continue reading

What is press-worthy scholarship?

StandardAs I was avoiding real work and morning traffic, there were a bunch of interesting things on twitter, as usual. Two things stood out.

First was a conversation among science writers, about how to find good science stories among press releases. I was wondering about all of the fascinating papers that never get press releases, but I didn’t want to butt into that conversation. Continue reading

Natural history, synthesis papers and the academic caste system

StandardIt’s been argued that in ecology, like politics, everything is local.

You can’t really understand ecological relationships in nature, unless you’re familiar with the organisms in their natural environment. Or maybe not. That’s probably not a constructive argument. My disposition is that good ecological questions are generated from being familiar with the life that organisms out of doors. But that’s not the only way to do ecology. Continue reading

Undergraduate research is many things

StandardConversations about “undergraduate research” often involve dispelling misconceptions.

Undergraduate research is not one thing.

What is undergraduate research? It is research that involves undergraduates. That’s all, nothing else. If you want it to mean something else, you might have to spell it out.

Collaboration keeps your research program alive

StandardIf you look at scientists in teaching-focused institutions who have robust research programs, there’s one thing they tend to have in common: They have active collaborations with researchers outside their own institution. Continue reading

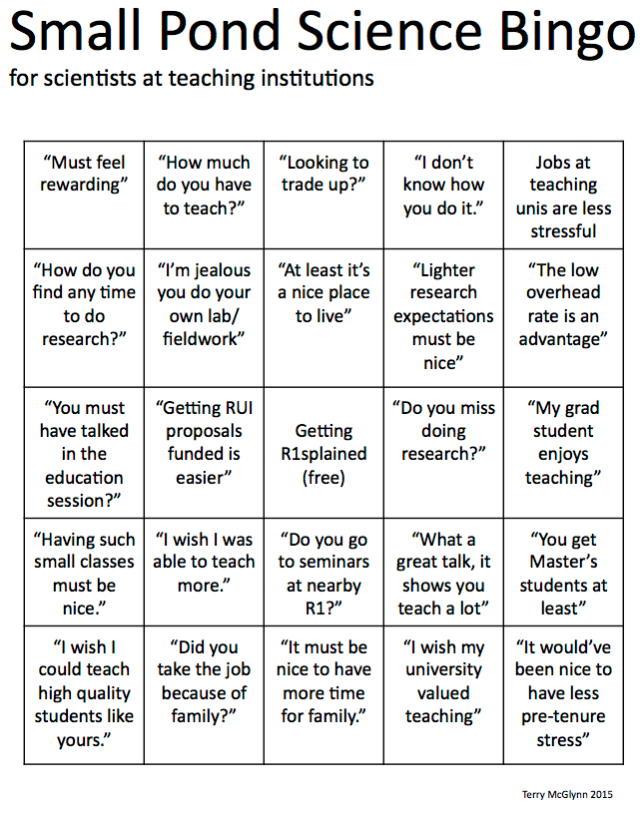

The Small Pond Science Bingo Card

StandardAre you interacting with colleagues from research institutions that have misconceptions about your job? Heading to a conference? Here’s a bingo card:

How to promote inclusivity in graduate fellowships?

StandardStudents who did their undergraduate work at elite universities are dominating access to federally funded graduate fellowships in the sciences. I pointed out this obvious fact at the beginning of this month, which to my surprise caught quite a bit of attention. I also got a lot of email (which I discuss here — it’s more interesting than you might expect).

A common response was: Okay, that’s the problem, what about solutions? Hence, this post. First, here are some facts that are are germane to the solutions. Continue reading

Elite vs. disadvantaged institutions, and NSF Graduate Fellowships: a peek inside the mailbag

StandardI’ll be soon be sharing specific ideas about what can be done about the disadvantages experienced by talented students who attend non-prestigious undergraduate institutions. But first, I thought it would be useful for me to share how this topic has affected my inbox.

I barely get any email related to this site. Aside from the site stats, and some interactions on twitter, I wouldn’t have any other indicator about readership. So when I receive the occasional email related to this site, it stands out.

In relative terms, I got several metric tons of emails about last week’s post about NSF graduate fellowships. Continue reading

Academic Moneyball

StandardOver the past week, I’ve been reading Moneyball, by Michael Lewis.

I’m not a baseball person (though I do keep tabs on football soccer). I found Moneyball to be interesting in its own right, but particularly when considering how its lessons may be applied to academic culture.

Lewis tells the story of Billy Beane, the manager of a small-budget major league baseball team, who assembled a crew that was better than most big-budget competitors. How did Beane pull this off?

According to Moneyball, Beane saw through the intellectually inbred and reality-challenged worldview that permeated the baseball community at the time. Scouts were picking players — and offering them humongous salaries — on the basis of athletic traits that didn’t help teams win games. Continue reading

Is it harder, or easier, to publish in your field?

StandardIt takes time and effort to publish a paper. After all, if it were really easy, then publications wouldn’t be a workable (albeit flawed) currency in for success in the sciences.

I often have heard about how some labs experience a bigger or smaller MPU (minimum publishable unit) than others, as I’ve worked in biology departments with a lot of academic diversity.

For example, I once knew an immunologist in an undergraduate institution who spent five years of consistently applied effort, to generate a single paper on a smallish-scale project. This wasn’t a problem in the department, as everyone accepted the notion that the amount of work that it took to generate a paper on this topic was greater than what it would take for (say) physiology, vertebrate paleontology, or ecology. Continue reading

Authorship when the first author is the senior author

StandardAuthorship conventions are based around assumptions that research was done under the umbrella of a research institution.

It’s often just fine to assume that the first author did the most work, and the last author is the senior author who is the PI of the lab that enabled the project.

That’s a fair assumption, so long as the senior author and the first author are different people. In my circumstance, when a paper comes out of my lab, I’m typically the first author and the senior author. Continue reading

What I said about my blog in my promotion file

StandardI’m periodically asked about the role of social media and blogs in my career and campus interactions. Here’s some information. Continue reading

Does your campus allow Federal Work Study awards for undergraduate research?

StandardI used to have Work-Study students doing research in my lab, when I was visiting faculty at Gettysburg College. Then I got a job somewhere else, and I couldn’t do that anymore.

The university where I now work does not assign Work-Study students to work with professors, just like my previous employer. There was a clear institutional policy that prohibited using Federal Work-Study awards to fill undergraduate research positions. Continue reading

Which institutions request external review for tenure files?

StandardToday, I’m submitting my file for promotion. It’s crazy to think I submitted my most recent tenure file five years ago, it feels closer to yesterday. Unless I get surprised (and it wouldn’t be the first time), I’ll be a full Professor if I’m here next year. And yet, throughout this entire process, there has been zero external validation of tenure and promotion. I think this is really odd. Continue reading

Chairing a search committee, in hindsight

StandardLast year, I had the dubious honor of chairing a search committee for two positions in my department. The speciality was open. I learned about my department and my university by seeing it through the eyes of applicants and would-be applicants. There’s a lot I’d like to say about the process that I can’t, or shouldn’t, say. But I do have some observations to share. Continue reading

One person’s story about post-PhD employment

StandardI’m an Associate Professor at a regional state university. How did I get here? What choices did I make that led me in this direction? This month, a bunch of folks are telling their post-PhD stories, led by Jacquelyn Gill. (This group effort constitutes a “blog carnival.”) Here’s my contribution.

I went to grad school because I loved to do research in ecology, evolution and behavior. I knew when I started that I’d be better off having been (meagerly) employed for five years to get a PhD.

The default career mode, at least at the time, was that grad students get a postdoc and then become a professor. It was understood that not everybody would want to, or be able to, follow this path. But is still the starting place in any discussion of post-PhD employment. As time progressed in grad school, I came to the conclusion that I didn’t want to run a lab at a research university, and that I wanted an academic position that combined research, teaching and some outreach.

I liked the idea of working at an R1 institution, but there were three dealbreakers. First, I didn’t want the grant pressure to keep my people employed and to maintain my own security of employment. Second, I wanted to keep it real and run a small lab so that I could be involved in all parts of the science. I didn’t want to be like all of the other PIs that only spent a few days in the field and otherwise were computer jockeys managing people and paper. Third, I was taught in grad school that the life of an R1 PI is less family-friendly than a faculty position at a non-R1 institution. In hindsight, now that I have worked at a few non-R1 institutions, I can tell you that these reasons are total bunk. I was naïve. My reasons for avoiding R1 institutions were not valid and not rooted in reality. Even though I now realize my reasons at the time were screwed up, I was primarily looking for faculty jobs at liberal arts colleges and other teaching-centered institutions.

We muddled through a two-body problem. My spouse wasn’t an academic, but needed a large city to work. She was early enough in her career that she was prepared to move for me while I did the postdoc job hop. I wouldn’t have wanted her to uproot from a good situation. In hindsight, our moves ended up being beneficial for both of us.

As I was approaching the finish to grad school, I was getting nervous about a job. My five years of guaranteed TA support were ending. I recall being very anxious. I landed a postdoc, though the only drawback was starting four months before defending my thesis. I moved from Colorado to Texas for my postdoc, and spent the day on the postdoc and the evenings finishing up my dissertation. As a museum educator, my spouse quickly found a job in the education department at the Houston Museum of Nature and Science.

While I was applying for postdocs, I also applied for faculty positions, even though I was still ABD. And surprisingly enough, I got a couple interviews. (I think I had 2-3 pubs at the time, one of which was in a fancy journal.) I got offered a 2-year sabbatical replacement faculty position at Gettysburg College, an excellent SLAC in south central Pennsylvania. At the same time, my spouse was deciding to go to grad school for more advanced training in museum education. By far, the best choice for her was to study at The George Washington University (don’t forget the ‘The’) in Washington, D.C. This seemed like a relatively magical convergence. With uncertainty for long-term funding in my postdoc (and also no shortage of problems with the project itself), we bailed on Texas and headed back east.

We lived in Frederick, Maryland. Which at the time was the only real city between Washington DC and Gettysburg. (Since then, I’ve heard it’s been converted into an exurb of DC.) I drove past the gorgeous Catoctin mountains every day to go to work, and she took car/metro into DC to work and started grad school. We scheduled her grad school so that she’d finish up when my two-year stint at Gettysburg would be over. I taught a full courseload for the first time, and noticed that I really liked the teaching/research gig at a small college. Grad school was great for my spouse. Life was good. In my first year as a Visiting Assistant Professor, I got four tenure-track job interviews.

Through a magical stroke of fortune, I got a tenure-track job offer in my wife’s hometown, in San Diego, just 2 to 5 hours away from my family in LA (depending on traffic). The only catch was that I’d have to leave my position at Gettyburg one year early, and my wife had one year left in grad school. But, I really needed to focus on starting out my tenure-track position, and she really had to focus on grad school. She could move to DC instead of splitting the commute with me, and I could figure out San Diego without her for a year. If kids were involved, this scenario would have been a lot more complicated. If my spouse’s career was at a more advanced stage, the move from grad school to postdoc to temporary faculty to tenure-track faculty would have a lot messier and would have required more compromises. But somehow we made it work and it felt something resembling normal.

Then, after working in San Diego for seven years, we moved up to Los Angeles. I already have told that story. Which, if you haven’t read it, is a nail-biter.

As I tell the story to non-academics, they find our peregrinations rather surprising. From LA, to Boulder, to Houston, to Maryland, to San Diego, and eventually back to LA, at least for the last seven years. (In the meanwhile, I’ve been going back and forth from my field site Costa Rica on a regular basis). This frequency of moving is entirely normal in academia, even if we look like vagabonds among our friends.

What do I offer as the take-home interpretations of my post-PhD job route?

First: The geography of my tenure-track job offers was lucky. To some extent, I’ve made this luck through persistence, but having landed a job in my wife’s hometown was pretty damn incredible. And after botching the first one entirely, getting one in my hometown was amazing. Now that my spouse is at the senior staff level, openings in her specialized field of museum education are about as rare and prized as in my own field. However, we now live in a big city with many universities and many world-class museums, so we can (theoretically) move jobs without moving our home. We now are juggling a three-body problem.

Second: My early choices constrained later options. Even though I no longer am wary of an R1 faculty position, after spending several years at teaching-focused universities that is a long shot for me. (I do several people who made that move, but it’s still a rarity.) I’m confident that I can operate a helluva research program at a highly-ranked R1, but I’m too senior for an entry-level tenure-track position, and not a rockstar who will be recruited for a senior-level hire. For example, I am confident that I would totally kick butt at UCLA just up the road, but I doubt a search committee there will reach the same conclusion. I am just as pleased to be at a non-prestigious regional university, and when I do move, it’ll be because I’ll be looking for better compensation and working conditions. I’m looking at working at all kinds of universities, and I think my job satisfaction will be more tied to local factors on an individual campus rather than the type of institution.

Third: I applied for jobs that many PhD students and postdocs think are unsuitable for themselves. I spent a lot of time creating applications for universities that I’ve never heard of. I was hired as an “ecosystem ecologist” at CSU Dominguez Hills in Los Angeles. Even though I grew up in Los Angeles, the first time I ever heard of CSU Dominguez Hills is when I saw the job ad. And I’m not an ecosystem ecologist either. That didn’t keep me from spending several hours tailoring my application for this particular job. But I wouldn’t have gotten this job unless I applied, and most postdocs are not applying for jobs like the one I have now. I know this from chairing a search committee for two positions last year. That’s a whole ‘nother story.

Fourth: Is being a professor my most favorite job ever? Actually, no. My employment paradise would be a natural history museum, with a mix of research, outreach and occasional teaching. I’m not a systematist or an evolutionary biologist, so getting hired into this kind of job is not likely. However, I have had a couple interviews for curatorial-esque positions over the last ten years and was exceptionally bummed that I didn’t get them. On the balance, even large museums go through phases of financial instability. It would be hard to give up tenure for a job that might bounce me to the street because of the financial misdeeds of board members and museum leadership. I’ve seen too many talented good museum people lose positions due to cutbacks or toxic administrators. I don’t know what could get me to take off the golden handcuffs of tenure. There are some university museums that hire faculty. That would be wonderful. Maybe someday that could happen. But I am pleased with what I’m doing, and I still am amazed that there are people paying me to do what I love.

Fifth: I ruled out a number of possibilities for family reasons. There are a variety of locations where I would be able to find work but would be unworkable for my spouse. Even in the depth of a job crisis, I opted against a number of options that would’ve given me strong and steady employment.

Sixth: I am not employed as a professor because I deserve it more than others. There are others equally, and more, deserving that are underemployed compared to my position in the academic caste system. The CV I had when I got my first academic position probably wouldn’t be able to do so now, 15 years later.

How much do you let students design projects?

StandardNow is the time of year when we work with students on designing summer research projects. How do you decide exactly what their project is, and how the experimental design is structured? This is something I struggle with.

In theory, quality mentorship (involving time, patience and skill) can lead a student towards working very independently and still have a successful project. Oftentimes, though, the time constraints involved in a summer project don’t allow for a comprehensive mentoring scheme that facilitates a high level of student independence. Should the goal of a student research project be training of an independently-thinking scientist or the production of publishable research? I think you can have both, but when push comes to shove, which way do you have to lean? I’ve written about this already. (Shorter: without the pubs, my lab would run out of dough and then no students would have any experiences. As is said, your mileage may vary.)

A well-designed project will require a familiarity with prior literature, experimental design, relevant statistical approaches and the ability to anticipate the objections that reviewers will have once the final product goes out for review. Undergraduates are typically lacking in most, if not all, of these traits. Sometimes you just gotta tell the student what will work and what will not, and what is important to the scientific community and what is not. And sometimes you can’t send the student home to read fifteen papers before reconsidering a certain technique or hypothesis.

When students in the lab are particularly excited about a project beyond my mentorable expertise, or beyond the realm of publishability, I don’t hesitate to advise a new course. I let them know what I hope students get out a summer research experience:

- a diverse social network of biologists from many subfields and universities

-

experience designing and running an experiment

-

a pub

All three of those things take different kinds of effort, but all three are within reach, and I make decisions with an effort to maximize these three things for the students. Which means that, what happens in my lab inhabits the right side of the continuum, sometimes on the edge of the ‘zone of no mentorship’ if I take on too many students.

You might notice one thing is missing from my list: conceive an experiment and develop the hypotheses being tested.

Students can do that in grad school if they want. Or in the lab of a different PI. I would rather have a students design experiments on hypotheses connected to my lab that I am confident can be converted into papers, rather than work on an experiments of the students’ own personal interest. (Most of my students become enamored of their experimental subnets pretty quickly, though.)

This approach is in the interest of myself to maintain a productive lab, but I also think that being handed a menu of hypotheses instead of a blank slate is also in the long-term interest of most students. I’m not keen on mentoring a gaggle of students who design their own projects when these projects are only for their edification, and not for sharing with the scientific community. That kind of thing is wonderful for the curriculum, but not for my research lab.

Other people have other approaches, and that is a Good Thing. We need many kinds of PIs, including those that give students so much latitude that they will have an opportunity to learn from failure. And also those that take on 1-2 students at a time and work with them very carefully. I like the idea of thinking about my approach to avoid falling into a default mode of mentorship. Does this scheme make sense, and if it does, where do you fit in and how have you made your choices? I would imagine the nature of your institution and the nature of your subfield — and how much funding is available — structures these choices.

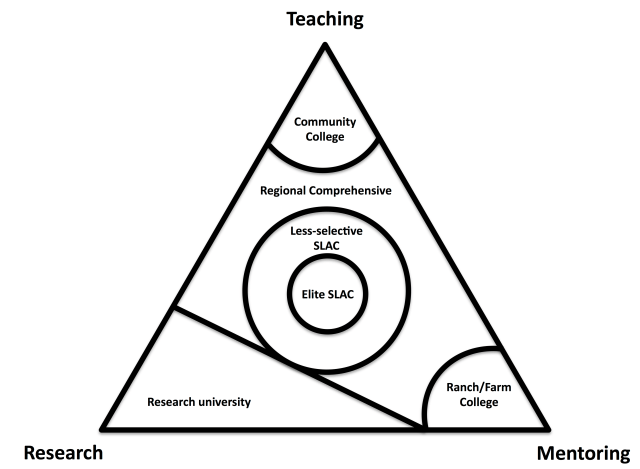

What kind of faculty job do you want?

StandardFaculty jobs involve teaching, research, and mentoring. Different kinds of universities expect faculty to conduct these activities in different proportions. What is your ideal balance? Consider the figure to find out where you belong.

Figure by T McGlynn

For the uninitiated, SLAC indicates “Small Liberal Arts College.”

This figure implies a lot of mechanisms that differentiate institutions, and there are a bunch of reasons why the distribution for a regional comprehensive (where I work currently) fills in the gaps that other institutions don’t occupy.

Why I prefer anonymous peer reviews

StandardNowadays, I rarely sign my reviews.

In general, I think it’s best if reviews are anonymous. This is my opinion as an author, as a reviewer, and as an editor. What are my reasons? Anonymous reviews might promote better science, facilitate a more even paying field, and protect junior scientists.

The freedom to sign reviews without negative repercussions is a manifestation of privilege. The use of signed reviews promotes an environment in which some have more latitude than others. When a tenured professor such as myself signs reviews, especially those with negative recommendations, I’m exercising liberties that are not as available to a PhD candidate.

To explain this, here I describe and compare the potential negative repercussions of signed and unsigned reviews.

Unsigned reviews create the potential for harm to authors, though this harm may be evenly distributed among researchers. Arguably, unsigned reviews allow reviewers to be sloppy and get away with a less-than-complete evaluation, which will cause the reviewer to fall out of the good graces of the editor, but not that of the authors. Also, reviewer anonymity allows scientific competitors or enemies to write reviews that unfairly trash (or more strategically sabotage) the work of one another. Junior scientists may not have as much social capital to garner favorable reviews from friends in the business as senior researchers. But on the other hand, anonymous reviews can mask the favoritism that may happen during the review process, conferring an advantage to senior researchers with a larger professional network.

Signed reviews create the potential for harm to reviewers, and confer an advantage to influential authors. It would take a brave, and perhaps foolhardy, junior scientist to write a thorough review of a poor-quality paper coming from the lab of an established senior scientist. This could harm the odds of landing a postdoc, getting a grant funded, or getting a favorable external tenure evaluation. Meanwhile, senior scientists may have more latitude to be critical without fear of direct effects on the ability to bring home a monthly paycheck. Signed reviews might allow more influential scientists to experience a breezier peer review experience than unknown authors.

When the identity of reviewers is disclosed, these data may result in more novel game theoretical strategies that may further subvert the peer-review process. For example, I know there are some reviewers out there who seem to really love the stuff that I do, and there is at least one (and maybe more) who appear to have it in for me. It would only be rational for me to list the people who give me negative reviews as non-preferred reviewers, and those who gave positive reviews as recommended reviewers. If I knew who they were. If everybody knew who gave them more positive and more negative reviews, some people would make choices to help them exploit the system to garner more lightweight peer review. The removal of anonymity can open the door to corruption, including tit-for-tat review strategies. Such a dynamic in the system would further exacerbate the asymmetries between the less experienced and more experienced scientists.

The use of signed reviews won’t stop people from sabotaging other papers. However signed reviews might allow more senior researchers to use their experience with the review system to exploit it in their favor. It takes experience receiving reviews, writing reviews, and handling manuscripts to anticipate the how editors respond to reviews. Of course, let’s not undersell editors, most of whom I would guess are savvy people capable of putting reviews in social context.

I’ve heard a number people say that signing their reviews forces them to write better reviews. This implies that some may use the veil of their identity to act less than honorably or at least not try as hard. (If you were to ask pseudonymous science bloggers, most would disagree.) While the content of the review might be substantially the same regardless of identity, a signed review might be polished with more varnish. I work hard to be polite and write a fair review regardless of whether I put my name on it. But I do admit that when I sign a review, I give it a triple-read to minimize the risk that something could be taken the wrong way (just as whenever I publish a post on this site). I wouldn’t intentionally say anything different when I sign, but it’s normal to take negative reviews personally, so I try to phrase things so that the negative feelings aren’t transferred to me as a person.

I haven’t always felt this way. About ten years ago, I consciously chose to sign all of my reviews, and I did this for a few years. I observed two side effects of this choice. The first one was a couple instances of awkward interactions at conferences. The second was an uptick in the rate which I was asked to review stuff. I think this is not merely a correlative relationship, because a bunch of the editors who were hitting me up for reviews were authors of papers that I had recently reviewed non-anonymously. (This was affirmation that I did a good job with my reviews, which was nice. But as we say, being a good reviewer and three bucks will get you a cup of coffee.)

Why did I give up signing reviews? Rejection rates for journals are high; most papers are rejected. Even though my reviews, on average, had similar recommendations as other reviewers, it was my name as reviewer that was connected to the rejection. My subfields are small, and if there’s someone who I’ve yet to meet, I don’t want my first introduction to be a review that results in a rejection.

Having a signed review is different than being the rejecting subject editor. As subject editor, I point to reviews to validate the decision, and I also have my well-reasoned editor-in-chief, who to his credit doesn’t follow subject editor recommendations in a pro forma fashion. The reviewer is the bad guy, not the editor. I don’t want to be identified as the bad guy unless it’s necessary. Even if my review is affirming, polite, and as professional as possible in a good way, if the paper is rejected, I’m the mechanism by which it’s rejected. My position at a teaching-focused institution places me on the margins of the research community, even if I am an active researcher. Why the heck would I put my name on something that, if taken the wrong way, could result in further marginalization?

When do I sign? There are two kinds of situations. First, some journals ask us to sign, and I will for high-acceptance rate journals. Second, if I recommend changes involving citations to my own work, I sign. I don’t think I’ve ever said “cite my stuff” when uncited, but sometimes a paper that cites me and follows up on something in my own work, and I step in to clarify. It would be disingenuous to hide my identity at that point.

The take home message on peer review is: The veil of anonymity in peer review unfairly confers advantages to influential researchers, but the removal of that veil creates a new set of more pernicious effects for less influential researchers.

–

Thanks to Dezene Huber whose remark prompted me to elevate this post from the queue of unwritten posts.

Negotiating for a faculty position: An anecdote, and what to do

StandardThis post is about a revoked job offer at a teaching institution that was in the news, and is also about how to negotiate for a job. I’ve written about negotiation priorities before, but this missive is about how to discuss those priorities with your negotiating partner.

Part A: That rescinded offer in the news

Last week, a story of outrage made the rounds. The capsule version is this: A philosopher is offered a job at a small teaching school. She tries to negotiate for the job. She then gets immediately punished for negotiating, by having the offer rescinded.

This story first broke on a philosophy blog, then into Inside Higher Ed, and some more mainstream media, if that’s what Jezebel is. There are a variety of other posts on the topic including this, and another by Cedar Reiner.

Some have expressed massive shock and appall. However, after reading the correspondence that caused the Dean to rescind the job offer, I’m not surprised at all. After initial conversations, the candidate wrote to the Dean:

As you know, I am very enthusiastic about the possibility of coming to Nazareth. Granting some of the following provisions would make my decision easier.

1) An increase of my starting salary to $65,000, which is more in line with what assistant professors in philosophy have been getting in the last few years.

2) An official semester of maternity leave.

3) A pre-tenure sabbatical at some point during the bottom half of my tenure clock.

4) No more than three new class preps per year for the first three years.

5) A start date of academic year 2015 so I can complete my postdoc.

I know that some of these might be easier to grant than others. Let me know what you think.

Here is what the Dean thought, in her words:

Thank you for your email. The search committee discussed your provisions. They were also reviewed by the Dean and the VPAA. It was determined that on the whole these provisions indicate an interest in teaching at a research university and not at a college, like ours, that is both teaching and student centered. Thus, the institution has decided to withdraw its offer of employment to you.

Thank you very much for your interest in Nazareth College. We wish you the best in finding a suitable position.

There has been a suggestion of a gendered aspect. That viewpoint is expressed well here, among other places. (There doesn’t seem to be a pay equity problem on this campus, by the way.) I wholly get the fact that aggressive negotiation has been seen as a positive trait for men and a negative trait for women. I think it is possible that gender played a role, but in my view, the explanation offered by the Dean is the most parsimonious one. (Now, my opinion will be dismissed by some because of my privilege as a tenured white dude. Oh well.) Given the information that we’ve been provided, and interpreted in light of my experiences at a variety of teaching campuses, I find the “fit” explanation credible, even if it’s not what I would have done.

A job offer is a job offer, and once an offer is made the employer should stand behind the offer. Then again, if some highly extraordinary events unfold before an agreement is reached, the institution can rescind the job offer. In this circumstance, is the candidate’s email highly extraordinary?

Did this start at “negotiation” communicate so many horrible things about the candidate that the institution should have pulled its offer? The Dean’s answer to that question was, obviously, “Yes.”

I would have answered “no.” Many others have done the yeoman’s blog work of explaining exactly how and and why that was the wrong answer to the question. I’m more interested in attempting to crawl inside the minds of the Dean and the Department that withdrew the offer. What were they thinking?

The blog that first broke this story called these items “fairly standard ‘deal-sweeteners.’” I disagree. If I try to place myself in the shoes of the Dean and the Department, then this is how I think I might have read that request:

I am not sure if I really want this position. If you are willing to stretch your budget more than you have for any other job candidate in the history of the college, then I might decide to take the job, because accepting it is not an easy decision.

1) I realize that your initial salary offer was about what Assistant Professors make at your institution, but I want to earn 20% more, as much as your Associate Professors, because that’s what new faculty starting at research universities get.

2) I’d know that 6 months of parental leave is unofficial policy and standard practice, but I want it in writing.

3) I’d like you to hire adjuncts for an extra sabbatical before I come up for tenure. By then I’m sure I’ll need a break from teaching, even though everybody else waits until after tenure to take a sabbatical.

4) Before I take this special extra sabbatical, I want an easier teaching schedule than everybody else in my department.

5) I want to stay in my postdoc for an extra year, because I’d rather do more research somewhere else than teach for you. I realize that you advertised the position to fill teaching needs, but you can hire an adjunct.

While some of these requests are the kind that I’d expect to be fulfilled by a research institution, I’m hoping that you are able to treat me like a professor from a research institution. Now that you’ve offered me this teaching job, I want my teaching obligations to be as minimal as possible. Let me know what you think.

And the Dean did exactly that: she let her know what she thought. I’m not really joking: that’s really how I think it could be seen, inside the context of a teaching- and student-centered institution.

Here is a more unvarnished version of what I imagine the Dean was thinking:

Holy moly! Who do you think we are? Don’t you realize that we want to hire you to teach? I didn’t pull the salary out of thin air, and it was aligned with what other new Assistant Professors earn here. And if you want to teach here, why the heck do you want to stay in your postdoc which presumably pays less money? If you wanted to stay in your for 18 months earning a postdoc salary, instead of coming to teach for us at a faculty-level salary, then why would you even want this job at all? Also, didn’t you realize that we advertised for the position to start this year because we need someone to teach classes in September? If you have such crazy expectations now, then I can only imagine what a pain in the butt you might be for us after you get tenure. I think it’s best if we dodge this bullet and you can try to not teach at a different university. We’re looking for someone who’s excited about teaching our students, and not as excited about finding ways to avoid interacting with them.

The fact remains that the candidate is actually seeking a teaching-centered position. However, she definitely was requesting things that an informed candidate would only ask from a research institution. I don’t think that she necessarily erred in making oversized requests, but her oversized requests were for the wrong things. They are focused on research, and not on teaching. While it might be possible that all of those requests were designed to improve the quality of instruction and the opportunities to mentor students, it clearly didn’t read that way to the Dean. We know it didn’t read that way, because the Dean clearly wrote that she thought the candidate was focused too heavily away from teaching and students. I’m not sure if that’s true, but based on the email, that perspective makes a heckvualotta sense to me.

I’d would be more inclined to chalk the unwise requests to some very poor advice about how to negotiate. I’d would have given the candidate a call and try to figure out her reasons, and if the answers were student-centered, then I’d continue the negotiation. But I can see how a reasonable Dean, Department, and Vice President of Academic Affairs could read that email and decide that the candidate was just too risky.

New tenure-track faculty hires often evolve into permanent commitments. You need to make the most of your pick. Hiring a dud is a huge loss, and it pays to be risk averse. If someone reveals that they might be a dud during the hiring process, the wise course of action is to pick someone who shows a lower probability of being a dud. However, once an offer is made, the interview is over.

But according to Nazareth College, this candidate showed her hand as a total dud, and a massive misfit for institutional priorities. Though I wouldn’t have done it, I have a hard time faulting them for pulling the offer. If they proceeded any further, they would have taken the chance that they’d wind up with an enthusiastic researcher who would have been avoiding students at every opportunity. Someone who might want to bail as soon as starting. Or maybe someone who got a better job while on the postdoc and not show up the next year. The department only has four tenure-track faculty, and would probably like to see as many courses taught by tenure-line faculty as possible.

Having worked in a few small ponds like Nazareth, I don’t see the outrageousness of these events. We really have no idea, though, because there is a lot of missing context. But we know that the Dean ran this set of pie-in-the-sky requests by the Department and her boss. They talked about it and made sure that they weren’t going to get into (legal) hot water and also made sure that they actually wanted to dump this candidate. It’s a good bet that the Department got this email and said, “Pull up, pull up! Abort!” They may have thought, “If we actually are lucky enough to fill another tenure-track line, we don’t want to waste it on someone who only wants to teach three preps before taking a pre-tenure sabbatical while we cover their courses.” I don’t know what they were thinking, of course, but this seems possible.

Karen Kelsky pointed out that offers are rescinded more often at “less prestigious institutions.” She’s definitely on to something. Less prestigious institutions have more weighty teaching loads and fewer resources for research (regardless of the cost of tuition). These are the kinds of institutions that are most likely to find faculty job candidates who are wholly unprepared for the realities of life on the job.

When an offer gets pulled, I imagine it’s because the institution sees that they’ve got a pezzonovante on their hands and they get out while they still can.

At teaching institutions, nobody wants a faculty member who shies away from the primary job responsibility: teaching.

In a research institution, how would the Dean and the Department feel if a job candidate asked the Dean for reduced research productivity expectations and a higher teaching load for the first few years? Wouldn’t that freak the Department out and show that they didn’t get a person passionate for research? Wouldn’t the Dean rethink that job offer? Why should it be any different for someone wanting to duck teaching at a teaching institution?

I don’t know what happened on the job interview, but that email from the candidate to the Dean is a huge red flag word embroidered with script that reads: “I don’t want to teach” and “I expect you to give me resources just like a research university would.” Of course everybody benefits when new faculty members get reassigned time to stabilize. But these requests were not just over the top, they were in orbit.

If I were the Dean at a teaching campus, what kinds of things would I want to see from my humanities job candidates? How about a guarantee for the chance to teach a specialty course? Funds to attend special conferences and funds to hire students as research assistants. Someone wanting to start early so that they could start curriculum development. Someone wanting a summer stipend to do research outside the academic year?

Here’s the other big problem I have with the narrative that has dogpaddled around this story. It’s claimed that the job offer was rescinded because she wanted to negotiate. But that’s not the case. The job candidate was not even negotiating.

Part B: What exactly is negotiation and how do you do it with a teaching institution?

A negotiation is a discussion of give and take. You do this for me, I do this for you. You give me the whip, and I’ll throw you the idol.

In the pulled offer at Nazareth College, the job candidate was attempting to “negotiate” like Satipo (the dude with the whip), but from other side of the gap.

What the Dean received from the candidate wasn’t even a start to a negotiation. It was, “Here is everything I want from you, how much can you give to me?” That is not a negotiation. A negotiation says, “Here are some things I’m interested in from you. If you give me these things, this is what I have to offer.”

How should this candidate have started the negotiation? Well, actually, the email should have been a request to schedule a phone conversation. What should the content of that conversation have been? How could the candidate have broached the huge requests (pre-tenure sabbatical, starting in 18 months, very few preps, huge salary)? By acknowledging that by providing these huge requests, huge output would come back.

“Once I get a contract for my second book, could you give me a pre-tenure sabbatical to write this book?”

“I’m concerned I won’t be able balance my schedule if I have too many preps early on. If you can keep my preps down to three per year, I’ll be more confident in my teaching quality and I should be able to continue writing manuscripts at the same time.”

“Right now, I am working on this exciting project during my postdoc, which is funded for another year. If it’s possible for me to arrive on campus after I finish my postdoc, this work will really help me create an innovative curriculum for [a course I will be teaching]. During this postdoc, I’d be glad to host some students from the college for internships and help them build career connections.” Of course, it’s very rare a teaching institution wants to wait a whole extra year. They want someone to teach, after all! It couldn’t hurt much to ask, if you phrase it like this, verbally.

“After running the numbers, I see that a salary of $65,000 is standard on the market for new faculty at sister institutions. But from what I’ve seen from the salary survey, this is well above the median salary for incoming faculty. If you can find the funds to bring me in at this salary, I’m okay if you trim back moving expenses. Being paid at current market rate in my field is important to me, and if you let me know what level of performance is tied to that level of compensation, I’ll deliver.”

By no means am I a negotiation pro. What I do know comes mostly from the classic book, “Getting to Yes.” The main point of this book is that “positional negotiation” is less likely to be successful. This approach involves opposite sides taking extreme positions and then finding a middle ground. Just like asking for a huge salary, and lots of reassigned time and easy teaching.

Getting to Yes explains how to do “principled negotiation.” In this case, you have a true negotiating partner in which you understand and respect one another’s interests. So, instead of haggling over salary like buying a used piece of furniture at a swap meet, you discuss the basis for the salary and what each of you will get out of it.

If you are asking for a reduced teaching load, then you explain what you will deliver with this reduced teaching load (higher quality teaching and more scholarship), and what the consequences will be if you don’t get it (potential struggle while teaching and fear that you won’t have time to do scholarship). And so on. The quotes I suggested above are what you’d expect to see in a principled negotiation. The book is a bit long but there are some critical ideas in there, and I’m really glad I read it before I negotiated my current position. When it was done, both I and the Dean thought we won, and we reached a fair agreement.

If you are in the position of receiving an academic job offer, negotiating for the best starting position is critical. You don’t have to be afraid of having the offer withdrawn as long as you’re negotiating in good faith. That mean you communicate an understanding the constraints and interests of your negotiating partner. And being sure that when you are ask for something, your reason is designed to fulfill the interests of your partner as much as yourself. So, asking for a bunch of different ways to get out of teaching responsibilities is a non-starter when your main job responsibility is teaching.

It’s not only acceptable to negotiate when you are starting an academic job, it’s expected. The worst lesson to take from this incident is Nazareth is that there is peril in negotiation. I suggest that the lesson is that you must negotiate. And, keep in mind that negotiation is a conversation and a partnership towards a common goal. Even when it comes to money, there is a common goal: You want to be paid enough that you’ll be happy and stay, and they want you to be paid enough that you’ll stay.

You won’t have anybody pull a job offer from you if you’re genuinely negotiating. It’s okay to ask for things that your negotiating partner can’t, or may not want to, deliver. However, what you ask for should reflect what you really truly want, and at the moment you’re asking, provide a clear rationale, so that you appear reasonable. If you’re interviewing for jobs, then I recommend picking up a copy of Getting to Yes.

I own my data, until I don’t.

StandardScience is in the middle of a range war, or perhaps a skirmish.

Ten years ago, I saw a mighty good western called Open Range. Based on the ads, I thought it was just another Kevin Costner vehicle. But Duncan Shepherd, the notoriously stingy movie critic, gave it three stars. I not only went, but also talked my spouse into joining me. (Though she needs to take my word for it, because she doesn’t recall the event whatsoever.)

The central conflict in Open Range is between fatcat establishment cattle ranchers and a band of noble itinerant free grazers. The free grazers roam the countryside with their cows in tow, chewing up the prairie wherever they choose to meander. In the time the movie was set, the free grazers were approaching extirpation as the western US was becoming more and more subdivided into fenced parcels. (That’s why they filmed it in Alberta.) To learn more about this, you could swing by the Barbed Wire Museum.

The ranchers didn’t take kindly to the free grazers using their land. The free grazers thought, well, that free grazing has been a well-established practice and that grass out in the open should be free.

If you’ve ever passed through the middle of the United States, you’d quickly realize that the free grazers lost the range wars.

On the prairie, what constitutes community property? If you’re on loosely regulated public land administered by the Bureau of Land Management, then you can use that land as you wish, but for certain uses (such as grazing), you need to lease it from the government. You can’t feed your cow for free, nowadays. That community property argument was settled long ago.

Now to the contemporary range wars in science: What constitutes community property in the scientific endeavor?

In recent years, technological tools have evolved such that scientists can readily share raw datasets with anybody who has an internet connection. There are some who argue that all raw data used to construct a scientific paper should become community property. Some have the extreme position that as soon as a datum is collected, regardless of the circumstances, it should become public knowledge as promptly as it is recorded. At the other extreme, some others think that data are the property of the scientists who created them, and that the publication of a scientific paper doesn’t necessarily require dissemination of raw data.

Like in most matters, the opinions of most scientists probably lie somewhere between the two poles.

The status quo, for the moment, is that most scientists do not openly disseminate their raw data. In my field, most new papers that I encounter are not accompanied with fully downloadable raw datasets. However, some funding agencies are requiring the availability of raw data. There are a few journals of which I am aware that require all authors to archive data upon publication, and there are many that support but do not require archiving.

The access to other people’s data, without the need to interact with the creators of the data, is increasing in prevalence. As the situation evolves, folks on both sides are getting upset at the rate of change – either it’s too slow, or too quick, or in the wrong direction.

Regardless of the trajectory of “open science,” the fact remains that, at the moment, we are conducing research in a culture of data ownership. With some notable exceptions, the default expectation is that when data are collected, the scientist is not necessarily obligated to make these data available to others.

Even after a paper is published, there is no broadly accepted community standard that the data that resulted in the paper become public information. On what grounds do I assert this? Well, last year I had three papers come out, all of which are in reputable journals (Biotropica, Naturwissenschaften, and Oikos, if you’re curious). In the process of publishing these papers, nobody ever even hinted that I could or should share the data that I used to write these papers. This is pretty good evidence that publishing data is not yet standard practice, though things are slowly moving in that direction. As evidence, I just got an email from Oikos as a recent author asking me to fill out a survey to let them know how I feel about data archiving policies for the journal.

As far as the world is concerned, I still own the data from those three papers published last year. If you ask me for the data, I’d be glad to share them with you after a bit of conversation, but for the moment, for most journals it seems to be my choice. I don’t think any of those three journals have a policy indicating that I need to share my dataset with the public. I imagine this could change in the near future.

I was chatting with a collaborator a couple weeks ago (working on “paper i”) and we were trying to decide where we should send the paper. We talked about PLOS ONE. I’ve sent one paper to this journal, actually one of best papers. Then I heard about a new policy of the journal to require public archiving of datasets from all papers published in the journal.

All of sudden, I’m less excited about submitting to this journal. I’m not the only one to feel this way, you know.

Why am I sour on required data archiving? Well, for starters, it is more work for me. We did the field and lab work for this paper during 2007-2009. This is a side project for everybody involved and it’s taken a long time to get the activation energy to get this paper written, even if the results are super-cool.

Is that my fault that it’ll take more work to share the data? Sure, it’s my fault. I could have put more effort into data management from out outset. But I didn’t, as it would have been more effort, and kept me from doing as much science as I have done. It comes with temporal overhead. Much of the data were generated by an undergraduate researcher, a solid scientist with decent data management practices. But I was working with multiple undergraduates in the field in that period of time, and we were getting a lot done. I have no doubts in the validity of the science we are writing up, but I am entirely unthrilled about cleaning up the dataset and adding the details into the metadata for the uninitiated. And, our data are a combination of behavioral bioassays, GC-MS results from a collaborator, all kinds of ecological field measurements, weather over a period of months, and so on. To get these numbers into a downloadable and understandable condition would be, frankly, an annoying pain in the ass. And anybody working on these questions wouldn’t want the raw data anyway, and there’s no way these particular data would be useful in anybody’s meta analysis. It’d be a huge waste of my time.

Considering the time it takes me to get papers written, I think it’s cute that some people promoting data archiving have suggested a 1-year embargo after publication. (I realize that this is a standard timeframe for GenBank embargoes.) The implication is that within that one year, I should be able to use that dataset for all it’s worth before I share it with others. We may very well want to use these data to build a new project, and if I do, then it probably would be at least a year before we head back to the rainforest again to get that project done. At least with the pace of work in my lab, an embargo for less than five years would be useless to me.

Sometimes, I have more than one paper in mind when I am running a particular experiment. More often, when writing a paper, I discover the need to write different one involving the same dataset (Shhh. Don’t tell Jeremy Fox that I do this.) I research in a teaching institution, and things often happen at a slower pace than at the research institutions which are home to most “open science” advocates. Believe it or not, there are some key results from a 15-year old dataset that I am planning to write up in the next few years, whenever I have the chance to take a sabbatical. This dataset has already been featured in some other papers.

One of the standard arguments for publishing raw datasets is that the lack of full data sharing slows down the progress of science. It is true that, in the short term, more and better papers might be published if all datasets were freely downloadable. However, in the long term, would everybody be generating as much data as they are now? Speaking only for myself, if I realized that publishing a paper would require the sharing of all of the raw data that went into that paper, then I would be reluctant to collect large and high-risk datasets, because I wouldn’t be sure to get as large a payoff from that dataset once the data are accessible.

Science is hard. Doing science inside a teaching institution is even harder. I am prone isolation from the research community because of where I work. By making my data available to others online without any communication, what would be the effect of sharing all of my raw data? I could either become more integrated with my peers, or more isolated from them. If I knew that making my data freely downloadable would increase interactions with others, I’d do it in a heartbeat. But when my papers get downloaded and cited I’m usually oblivious to this fact until the paper comes out. I can only imagine that the same thing could happen with raw data, though the rates of download would be lower.

In the prevailing culture, when data are shared, along with some other substantial contributions, that’s standard grounds for authorship. While most guidelines indicate that providing data to a collaborator is not supposed to be grounds for authorship, the current practice is that it is grounds for authorship. One can argue that it isn’t fair nor is it right, but that is what happens. Plenty of journals require specification of individual author contributions and require that all authors had a substantial role beyond data contribution. However, this does not preclude that the people who provide data do not become authors.

In the culture of data ownership, the people who want to write papers using data in the hands of other scientists need to come to an agreement to gain access to these data. That agreement usually involves authorship. Researchers who create interesting and useful data – and data that are difficult to collect – can use those data as a bargaining chip for authorship. This might not be proper or right, and this might not fit the guidelines that are published by journals, but this is actually what happens.

This system is the one that “open science” advocates want to change. There are some databases with massive amounts of ecological and genomic data that other people can use, and some people can go a long time without collecting their own data and just use the data of others. I’m fine with that. I’m also fine with not throwing my data in to the mix.

My data are hard-won, and the manuscripts are harder-won. I want to be sure that I have the fullest opportunity to use my data before anybody else has the opportunity. In today’s marketplace of science, having a dataset cited in a publication isn’t much credit at all. Not in the eyes of search committees, or my Dean, or the bulk of the research community. The discussion about the publication of raw data often avoids tacit facts about authorship and the culture of data ownership.

To be able to collect data and do science, I need grant money.

To get grant money, I need to give the appearance of scientific productivity.

To show scientific productivity, I need to publish a bunch of papers.

To publish a bunch of papers, I need to leverage my expertise to build collaborations.

To leverage my expertise to build collaborations, I need to have something of quality to offer.

To have something of quality to offer, I need to control access to the data that I have collected. I don’t want that to stop after publication.

The above model of scientific productivity is part of the culture of data ownership, in which I have developed my career at a teaching institution. I’m used to working amicably and collaboratively, and the level of territoriality in my subfields is quite low. I’ve read the arguments, but I don’t see how providing my data with no strings attached would somehow build more collaborations for me, and I don’t see how it would give me any assistance in the currency that matters. I am sure that “open science” advocates are wholly convinced that putting my data online would increase, rather than constrict opportunities for me. I am not convinced, yet, though I’m open to being convinced. I think what will convince me is seeing a change in the prevailing culture.

There is one absurdity to these concerns of mine, that I’m sure critics will have fun highlighting. I doubt many people would be downloading my data en masse. But, it’s not that outlandish, and people have done papers following up on my own work after communicating with me. I work at a field site where many other people work; a new paper comes out from this place every few days. I already am pooling data with others for collaborations. I’d like to think that people want to work with me because of what I can bring to the table other than my data, but I’m not keen on testing that working hypothesis.

Simply put, in today’s scientific rewards system, data are a currency. Advocates of sharing raw data may argue that public archiving is like an investment with this currency that will yield greater interest than a private investment. The factors that shape whether the yield is greater in a public or private investment of the currency of data are complicated. It would be overly simplistic to assert that I have nothing to lose and everything to gain by sharing my raw data without any strings attached.

While good things come to those who are generous, I also have relatively little to give, and I might not be doing myself or science a service if I go bankrupt. Anybody who has worked with me will report (I hope) that am inclusive and giving with what I have to offer. I’ve often emailed datasets without people even asking for them, without any restrictions or provisions. I want my data to be used widely. But even more, I want to be involved when that happens.

Because I run a small operation in a teaching institution, my research program experiences a set of structural disadvantages compared to colleagues at an R1 institution. The requirement to share data levies the disadvantage disproportionately against researchers like myself, and others with little funding to rapidly capitalize on the creation of quality data.

To grow a scientific paper, many ingredients are required. As grass grows the cow, data grows a scientific paper.

In Open Range, the resource in dispute is not the grass, but the cows. The bad guy ranchers aren’t upset about losing the grass, they just don’t want these interlopers on their land. It’s a matter of control and territoriality. At the moment, the status quo is that we run our own labs, and the data growing in these labs are also our property.

When people don’t want to release their data, they don’t care about the data itself. They care about the papers that could result from these data. I don’t care if people have numbers that I collect. What I care about is the notion that these numbers are scientifically useful, and that I wish to get scientific credit for the usefulness of these numbers. Once the data are public, there is scant credit for that work.

It takes plenty of time and effort to generate data. In my case, lots of sweat, and occasionally some venom and blood, is required to generate data. I also spend several weeks per year away from my family, which any parent should relate with. Many of the students who work with me also have made tremendous personal investments into the work as well. Generating data in my lab often comes at great personal expense. Right now, if we publicly archived data that were used in the creation of a new paper, we would not get appropriate credit in a currency of value in the academic marketplace.

When a pharmaceutical company develops a new drug, the structure of the drug is published. But the company has a twenty year patent and five years of exclusivity. It’s widely claimed – and believed – that without the potential for recouping the costs of work in developing medicines that pharmaceutical companies wouldn’t jump through all the regulatory hoops to get new drugs on the market. The patent provides incentive for drug production. Some organizations might make drugs out of the goodness of their hearts, but the free market is driven by dollars. An equivalent argument could be wagered for scientists wishing for a very long time window to reap the rewards of producing their own data.

In the United States, most meat that people consume doesn’t come from grass on the prairie, but from corn grown in an industrial agricultural setting. Likewise, most scientific papers that get published come from corn-fed data produced by a laboratory machine designed to crank out a high output of papers. Ranchers stay in business by producing a lot of corn, and maximizing the amount of cow tissue that can be grown with that corn. Scientists stay in business by cranking out lots of data and maximizing how many papers can be generated from those data.

Doing research in a small pond, my laboratory is ill equipped to compete with the massive corn-fed laboratories producing many heads of cattle. Last year was a good year for me, and I had three papers. That’s never going to be able to compete with labs at research institutions — including the ones advocating for strings-free access to everybody’s data.

The movement towards public data archiving is essentially pushing for the deprivatization of information. It’s the conversion of a private resource into a community resource. I’m not saying this is bad, but I am pointing out this is a big change. The change is biggest for small labs, in which each datum takes a relatively greater effort to produce, and even more effort to bring to publication.

So far, what I’ve written is predicated on the notion that researchers (or their employers) actually have ownership of the data that they create. So, who actually owns data? The answer to that question isn’t simple. It depends on who collected it, who funded the collection of the data, and where the data were published.

If I collect data on my own dime, then I own these data. If my data were collected under the funding support of an agency (or a branch of an agency) that doesn’t require the public sharing of the raw data, then I still own these data. If my data are published in a journal that doesn’t require the publication of raw data, I still own these data.

It’s fully within the charge of NIH, NSF, DOE, USDA, EPA and everyone else to require the open sharing of data collected under their support. However, federal funding doesn’t necessarily necessitate public ownership (see this comment in Erin McKiernan’s blog for more on that.) If my funding agency, or some federal regulation, requires that my raw data be available for free downloads, then I no longer own these data. The same is true if a journal has a similar requirement. Also, if I choose to give away my data, then I no longer own them.

So, who is in a position to tell me when I need to make my data public? My program officer, or my editor.

If you wish, you can make it your business by lobbying the editors of journals to change their practices, and you can lobby your lawmakers and federal agencies for them to require and enforce the publication of raw datasets.

I think it’s great when people choose to share data. I won’t argue with the community-level benefits, though the magnitude of these benefits to the community vary with the type of data. In my particular situation, when I weigh the scant benefit to the community relative to the greater cost (and potential losses) to my research program, the decision to stay the course is mighty sensible.

There are some well-reasoned folks, who want to increase the publication of raw datasets, who understand my concerns. If you don’t think you understand my concerns, you really need to read this paper. In this paper, they had four recommendations for the scientific community at large, all of which I love:

Facilitate more flexible embargoes on archived data

Encourage communication between data generators and re-users

Disclose data re-use ethics

Encourage increased recognition of publicly archived data.

(It’s funny, in this paper they refer to the publication of raw data as “PDA” (public data archiving), but at least here in the States, that acronym means something else.)

And they’re right, those things will need to happen before I consider publishing raw data voluntarily. Those are the exact items that I brought up as my own concerns in this post. The embargo period would need to be far longer, and I’d want some reassurance that the people using my data will actually contact me about it, and if it gets re-used, that I have a genuine opportunity for collaboration as long as my data are a big enough piece. And, of course, if I don’t collaborate, then the form of credit in the scientific community will need to be greater than what happens now, which is getting just cited.

The Open Data Institute says that “If you are publishing open data, you are usually doing so because you want people to reuse it.” And I’d love for that to happen. But I wouldn’t want it to happen without me, because in my particular niche in the research community, the chance to work with other scientists is particularly valuable. I’d prefer that my data to be reused less often than more often, as long as that restriction enabled me more chances to work directly with others.

Scientists at teaching institutions have a hard time earning respect as researchers (see this post and read the comments for more on that topic). By sharing my data, I realize that I can engender more respect. But I also open myself up to being used. When my data are important to others, then my colleagues contact me. If anybody feels that contacting me isn’t necessary, then my data are not apparently necessary.

Is public data archiving here to stay, or is it a passing fad? That is not entirely clear.

There is a vocal minority that has done a lot to promote the free flow of raw data, but most practicing scientists are not on board this train. I would guess that the movement will grow into an establishment practice, but science is an odd mix of the revolutionary and the conservative. Since public data archiving is a practice that takes extra time and effort, and publishing already takes a lot work, the only way will catch on is if it is required. If a particular journal or agency wants me to share my data, then I will do so. But I’m not, yet, convinced that it is in my interest.

I hope that, in the future, I’ll be able to write a post in which I’m explaining why it’s in my interest to publish my raw data.

The day may come when I provide all of my data for free downloads, but that day is not today.

I am not picking up a gun in this range war. I’ll just keep grazing my little herd of cows in a large fragment of rainforest in Sarapiquí, Costa Rica until this war gets settled. In the meantime, if you have a project in mind involving some work I’ve done, please drop me a line. I’m always looking for engaged collaborators.

NSF mostly overlooked teaching institutions for Presidential Early Career Awards

StandardThe PECASE awards from NSF were announced as a Christmas present for 19 scientists.

These Presidential Early Career Awardees are picked from the cream of the crop of the CAREER awards. The CAREER award emphasizes an integrated research and teaching career development plan. Hearty congratulations to all recipients! This should make the holiday even nicer.

This year’s recipients of NSF PECASE awards work at the following institutions. Undergraduate institutions are in bold.

Alabama

Arizona

Berkeley (x2)

BYU

Bowdoin

Caltech

Cornell

Georgia Tech

Louisville

Maryland

Minnesota

Princeton

Santa Barbara

Stanford

Univ. Puerto Rico at Cayey (classification here)

Texas

Virginia Tech

Wisconsin

Selection for this award is based on two important criteria: 1) innovative research at the frontiers of science and technology that is relevant to the mission of the sponsoring organization or agency, and 2) community service demonstrated through scientific leadership, education or community outreach.

This year, if you round up, then 11% of these PECASE awards from via NSF went to scientists at primarily undergraduate institutions. If you browse the institutions with CAREER awardees, it’s clear that this nonrandom subset has a bias against the awardees from teaching institutions. There are far more than 11% CAREER awardees from teaching institutions.

Is this bias based on merit? That’s an interesting question. How is merit quantified by NSF when picking PECASE awards from among the CAREER awards? I have no idea how to answer that question.

I don’t find any of this surprising, but thought that I should put this fact out there. Those of you are applying for CAREERs from teaching institutions have a good shot at getting one, but, well, don’t make the mistake of thinking you have a fair shot at the PECASE. For the two of you who cracked that very hard nut this year, congratulations!

Does being a “Jack-of-all-Trades” impede or facilitate an early-stage academic career?

StandardThis is a guest post by Andrea Kirkwood. She is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Science at UOIT, and you can follow on twitter at @KirkwoodLab

Jack-of-all-Trades, Master of Nothing

Recently a topic near and dear to my heart came up on Twitter. Allison Barner (@algaebarnacle) was live-tweeting from the Western Society of Naturalists meeting, and posted the following tweet:

https://twitter.com/algaebarnacle/status/398900875646607361

This tweet caught my attention, because it touched on an issue that caused some anxiety for me as I completed my doctoral degree. At the time, I thought my graduate school training was too broad, straddling several disciplines (ecology, phycology and microbiology) across very different systems (lakes vs. wastewater lagoons). Some may view this is a strength, bringing to mind the classical view of what a Doctor of Philosophy should be. Yet at the time I was completing my Ph.D. (circa 2002), I suspected that my skill-set was viewed as old-fashioned, and was being supplanted by the next-wave of sexy techniques. I also felt like I knew a little about a lot of things, but an expert in nothing. Sound familiar? I attempted to rectify this by choosing to do my first post-doc in a lab where I could learn a sexy technique (i.e., applying molecular methods in phylogeny and diversity assessment). Becoming adept at a special skill had to be the right move because several of my peers were getting faculty positions based on their “special skills”. You’re a quantitative ecologist, we’ll hire you! You use the latest molecular technique, we’ll hire you! It seemed that if you had a specific, timely skill-set, you were highly marketable. The message was that Jack-of-all-Trades (JOAT) need not apply.

Still, I wasn’t personally satisfied with just learning the latest sexy tools. When an opportunity came up to do something completely different for my next post-doc, I jumped at the chance. Not only would I get to work in a new system (rivers of the Canadian Rockies), but learn more about theoretical ecology. Here I was expanding my academic repertoire yet again to the detriment of specialization. One could blame my lengthy sojourn as a post-doc (5.5 years) on not having an obvious niche research area. Nonetheless, my academic breadth made it possible to apply to a broad swath of jobs, and end up on interview short-lists. Based on some feedback though, it was apparent that search committees either found it difficult to pigeon-hole my research area, or didn’t think I quite fit the specialization they were looking for.

I was very fortunate to be hired by a new university in Canada that didn’t have the luxury of hiring specialists. They needed someone who could teach a broad selection of biology courses, as well as have an applied research angle to fulfill their STEM mandate. This was an extremely rare kind of faculty hire at a Canadian research university. In the United States, this is apparently the typical hiring emphasis for small, teaching-focused universities as vouched by Terry McGlynn (@hormiga) on Twitter:

https://twitter.com/hormiga/status/398908528271695872

Although I breathed a sigh of relief upon securing a tenure-track faculty position, I then had to fret about the views of research-funding committees. I know several colleagues who were denied funding, in part, because they could not convince the reviewers they were expert enough. To add to my angst, the Great Recession had begun and the current government was slashing and burning research funding. Ironically, it was these dire funding circumstances that showcased the strengths of being an academic JOAT. I quickly discovered that I could access a broader pool of funding sources compared to my specialist colleagues. I secured grants in ecology, conservation, and biotechnology. Now one could argue this approach allows funding agencies to direct your research program (i.e., tail wagging the dog), which is true to some extent. Ultimately, the researcher has to decide to what degree they will chase money this way, and perhaps only use this funding model during the lean years. In my mind, if it can keep your lab running and let you and your students continue to do science, it certainly has its merits.

So admittedly up to this point, I have provided a narrative that asserts my credentials as a card-carrying JOAT. What does that mean exactly? Am I really a Master of Nothing? The very nature of grad school is to become a specialist at something, at least compared to the general population. Along the way, grad students and post-docs acquire specialized skills in their fields, some more than others. Serendipitously, I became a leading expert on Didymosphenia geminata (aka “Didymo” or “rock snot”) during my second post-doc, and will unabashedly credit D. geminata for saving my career (a blog entry for another day). Does this mean I lose the right to claim the JOAT label at all?

Brett Favaro (@brettfavaro) sums it up nicely by stating: