Last month, l linked to a series of posts about my job search after tenure denial, and how I settled into my current job. Here is the promised follow-up to put my tenure denial ordeal, now more than seven years ago, in some deeper context.

As I was getting denied tenure, nobody suggested that tenure denial was actually a blessing. Nevertheless, if anybody would have had the temerity to make such a suggestion, they’d have been right.

I don’t feel a need to get revenge on the people who orchestrated the tenure denial. But if the best revenge is living well, then I’m doing just fine in that department. I’m starting my fourth year as an Associate Professor of Biology in my hometown. Without asking, I was given the green light to go up for promotion to full Professor two years early. In the last few years, I received a university-wide research award and I was elected to a position of honor in my professional society. I feel that all aspects of my work are valued by those who matter, especially the students in my lab. I’ve managed to keep my lab adequately funded, which is no small matter nowadays. Less than a year ago, I started this blog. That’s been working out well.

The rest of my family is also faring well, professionally and personally. We are integrated into the life of our town. We have real friendships, and life is busy, fun and rewarding.

I’m high enough on life that I don’t often reflect on the events surrounding my tenure denial. There’s nothing to be gained by dedicating any synapses to the task. Three years ago, I wrote that hindsight didn’t help me understand why I was denied tenure. One might think that a few more years wouldn’t add additional hindsight. But a recent surprise event put things in perspective.

As part of work for some committees, I’ve been reading a ton of recommendation letters. One of these letters was written for someone who I know quite well, and the letter was written by my former colleague, “Bob.” (I don’t want to out the person for whom the letter was written, so I have to keep things vague.) This letter was both a revelation and a punch to the gut.

Bob was a mentor to me. He was an old hand who knew where the bodies were buried and was an experienced teacher. I knew Bob well, and I thought I understood him. When came upon Bob’s recommendation letter for this other person I know, I was stunned.

Bob primarily wrote in detail about a single and irreparable criticism, and then garnished the letter with faint praise. The two-page letter was written with care. Based on how well I know Bob, or how well I thought I knew him, I am mighty sure that it was not written with any intention of a negative recommendation. (I also happen to know the person about whom the letter was written better than Bob, and it’s also clear that the letter was off the mark.)

Being familiar with Bob’s style, if not his recommendation-writing acumen, I clearly see that he thought he was writing a strong positive letter, short of glowing, and that he was doing a good deed for the person for whom he wrote the letter. He didn’t realize in any way that he was throwing this person under the bus.

How could Bob’s judgment be so clouded? I am pretty sure he merely thought that he was providing an honest assessment to enhance the letter’s credibility. In hindsight, I see that Bob often supported others with ample constructive criticism. (For example, he once gave me a friendly piece of advice, without a dram of sarcasm, that I was making a “huge mistake” by choosing to have only one child.)

It didn’t take long for me to connect some dots.

I remembered something that my former Dean mentioned about his recommendation to the independent college committee (which oddly enough, also included the Dean as a member): the letters from my department were “not positive enough.” (I never had access to any of these letters.) Because my department, and Bob in particular, claimed to support me well, I found this puzzling.

At the time, I suspected that the Dean’s remarks reflected the lack of specific remarks and observations, as most of my colleagues skipped the required task of observing me in the classroom, despite my regular requests. Presumably nobody bothered to visit my classroom because they thought I was meeting their standards.

Then I recalled that one of the few colleagues who actually visited my classroom on a regular basis was Bob. Did his letter for me look like the one that I just read? Did he write that my teaching had some positive attributes, but I that my performance fell short of his standards for a variety of reasons?

Did Bob try to offer some carefully nuanced observations to lend credibility but, instead, inadvertently wrote a hit piece? That seems likely.

Considering the doozy of a letter that he wrote for this other person who I know well, it’s hard to imagine that he even knows how to write a supportive recommendation letter. Since he was my closest mentor and the only other person in my subfield, I’m chilled to think of what he wrote for my secret tenure file.

Meanwhile, it’s likely that my other official mentor wrote a brief, weak, letter, because he couldn’t even spare the time to review the narrative for my tenure file before I submitted it to the department. Thanks to the everlasting memory of gmail, check out what I just dug out of my mailbox:

So, why was I denied tenure? It’s not Bob’s fault for writing a bad letter. The most parsimonious conclusion is that I just didn’t fit in.

I saw my job differently. At the time, I would have disagreed with that assessment. But now, I see how I didn’t fit. The fact that I didn’t even realize that Bob would be writing bad recommendation letters shows how badly my lens was maladjusted. If I fit in better, I would have been able to anticipate and prepare for that eventuality. I trusted the wrong people and was myopic in a number of ways, including how others saw me. I probably still am too myopic in that regard.

How was I different? I emphasized research more, but I also worked with students in a different manner. Since I’ve left, my trajectory has continued even further away from the emphasis of my old department. I’m teaching less as my research and administrative obligations grow, and my lab’s productivity is greater than could have been tolerated in my old department. My lab is full of extraordinary students that would have been sorely out of place in my old university.

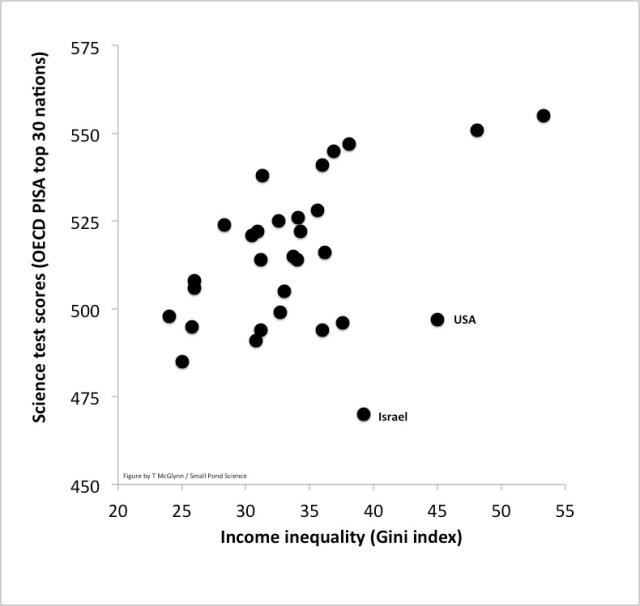

I work in a public university with students whom my former colleagues would call “poor quality.” I am changing more individual lives than I ever could have before, by giving students with few options opportunities that they otherwise could not access.

It is fitting that my current position, at a university that gives second chances to underprepared students from disadvantaged backgrounds, is also a second chance for myself.

I might not have gotten tenure in my last job, but I had lots of opportunities to work with students. These interactions transcended employment; they were mutualistic and some have evolved into friendships. I look on my time there with great fondness, despite the damage that my former colleagues inflicted on me. I am gratified that I made the most in an environment where I didn’t belong.

I hope that it is obvious to those who know me and how I do my job, that my tenure denial does not make me look bad, but makes my former institution look bad. If I were to draw that conclusion at the time it happened, it would seem like, and would have been, sour grapes. Now that more time has passed, I’m inclined to believe the more generous interpretation that others have proffered.

I resisted that interpretation for a long time, because others would correctly point out that I would be the worst person to make such an assessment. I still have that bias, but I also have more information and the perspective of seven years. Is it possible that my post-hoc assessment paints a skewed picture of what happened? Of course; I can’t be objective about what happened. If I have any emotion about that time, it’s primarily relief: not just that I found another job, but that I found one where people make me feel like I belong.

I don’t stay in touch with anybody in my old department, as I snuck away as quietly as possible. Tenure denial is a rough experience, and I didn’t have it in me to maintain a connection with my department mates, even those who claimed to be supportive. We had little in common, other than a love for biology and a love for teaching, but both of those passions manifested quite differently.

I don’t have any special wisdom to offer other professors that have the misfortune of going through tenure denial. Tenure denial was the biggest favor I’ve ever received in my professional life, but I wouldn’t recommend it for anyone else. If it were not for tremendously good luck, I probably would have been writing far grimmer report.

Update: After a couple conversations I realize I should clarify how evaluation letters worked where I was denied. In the system at that time, every professor in the department is required to write an evaluation letter that goes straight into the file. These are all secret evaluations and it’s expected that the candidate is not aware of what is in the letters. If I had the option of asking people to write letters, I don’t think I ever would have asked Bob to write a letter for me, because I had several colleagues who I knew would write me great ones. The surprise about Bob was had the capacity to write such a miserably horrible letter and not even realize it. He is even worse at nuance than I expected.