Science is in the middle of a range war, or perhaps a skirmish.

Ten years ago, I saw a mighty good western called Open Range. Based on the ads, I thought it was just another Kevin Costner vehicle. But Duncan Shepherd, the notoriously stingy movie critic, gave it three stars. I not only went, but also talked my spouse into joining me. (Though she needs to take my word for it, because she doesn’t recall the event whatsoever.)

The central conflict in Open Range is between fatcat establishment cattle ranchers and a band of noble itinerant free grazers. The free grazers roam the countryside with their cows in tow, chewing up the prairie wherever they choose to meander. In the time the movie was set, the free grazers were approaching extirpation as the western US was becoming more and more subdivided into fenced parcels. (That’s why they filmed it in Alberta.) To learn more about this, you could swing by the Barbed Wire Museum.

The ranchers didn’t take kindly to the free grazers using their land. The free grazers thought, well, that free grazing has been a well-established practice and that grass out in the open should be free.

If you’ve ever passed through the middle of the United States, you’d quickly realize that the free grazers lost the range wars.

On the prairie, what constitutes community property? If you’re on loosely regulated public land administered by the Bureau of Land Management, then you can use that land as you wish, but for certain uses (such as grazing), you need to lease it from the government. You can’t feed your cow for free, nowadays. That community property argument was settled long ago.

Now to the contemporary range wars in science: What constitutes community property in the scientific endeavor?

In recent years, technological tools have evolved such that scientists can readily share raw datasets with anybody who has an internet connection. There are some who argue that all raw data used to construct a scientific paper should become community property. Some have the extreme position that as soon as a datum is collected, regardless of the circumstances, it should become public knowledge as promptly as it is recorded. At the other extreme, some others think that data are the property of the scientists who created them, and that the publication of a scientific paper doesn’t necessarily require dissemination of raw data.

Like in most matters, the opinions of most scientists probably lie somewhere between the two poles.

The status quo, for the moment, is that most scientists do not openly disseminate their raw data. In my field, most new papers that I encounter are not accompanied with fully downloadable raw datasets. However, some funding agencies are requiring the availability of raw data. There are a few journals of which I am aware that require all authors to archive data upon publication, and there are many that support but do not require archiving.

The access to other people’s data, without the need to interact with the creators of the data, is increasing in prevalence. As the situation evolves, folks on both sides are getting upset at the rate of change – either it’s too slow, or too quick, or in the wrong direction.

Regardless of the trajectory of “open science,” the fact remains that, at the moment, we are conducing research in a culture of data ownership. With some notable exceptions, the default expectation is that when data are collected, the scientist is not necessarily obligated to make these data available to others.

Even after a paper is published, there is no broadly accepted community standard that the data that resulted in the paper become public information. On what grounds do I assert this? Well, last year I had three papers come out, all of which are in reputable journals (Biotropica, Naturwissenschaften, and Oikos, if you’re curious). In the process of publishing these papers, nobody ever even hinted that I could or should share the data that I used to write these papers. This is pretty good evidence that publishing data is not yet standard practice, though things are slowly moving in that direction. As evidence, I just got an email from Oikos as a recent author asking me to fill out a survey to let them know how I feel about data archiving policies for the journal.

As far as the world is concerned, I still own the data from those three papers published last year. If you ask me for the data, I’d be glad to share them with you after a bit of conversation, but for the moment, for most journals it seems to be my choice. I don’t think any of those three journals have a policy indicating that I need to share my dataset with the public. I imagine this could change in the near future.

I was chatting with a collaborator a couple weeks ago (working on “paper i”) and we were trying to decide where we should send the paper. We talked about PLOS ONE. I’ve sent one paper to this journal, actually one of best papers. Then I heard about a new policy of the journal to require public archiving of datasets from all papers published in the journal.

All of sudden, I’m less excited about submitting to this journal. I’m not the only one to feel this way, you know.

Why am I sour on required data archiving? Well, for starters, it is more work for me. We did the field and lab work for this paper during 2007-2009. This is a side project for everybody involved and it’s taken a long time to get the activation energy to get this paper written, even if the results are super-cool.

Is that my fault that it’ll take more work to share the data? Sure, it’s my fault. I could have put more effort into data management from out outset. But I didn’t, as it would have been more effort, and kept me from doing as much science as I have done. It comes with temporal overhead. Much of the data were generated by an undergraduate researcher, a solid scientist with decent data management practices. But I was working with multiple undergraduates in the field in that period of time, and we were getting a lot done. I have no doubts in the validity of the science we are writing up, but I am entirely unthrilled about cleaning up the dataset and adding the details into the metadata for the uninitiated. And, our data are a combination of behavioral bioassays, GC-MS results from a collaborator, all kinds of ecological field measurements, weather over a period of months, and so on. To get these numbers into a downloadable and understandable condition would be, frankly, an annoying pain in the ass. And anybody working on these questions wouldn’t want the raw data anyway, and there’s no way these particular data would be useful in anybody’s meta analysis. It’d be a huge waste of my time.

Considering the time it takes me to get papers written, I think it’s cute that some people promoting data archiving have suggested a 1-year embargo after publication. (I realize that this is a standard timeframe for GenBank embargoes.) The implication is that within that one year, I should be able to use that dataset for all it’s worth before I share it with others. We may very well want to use these data to build a new project, and if I do, then it probably would be at least a year before we head back to the rainforest again to get that project done. At least with the pace of work in my lab, an embargo for less than five years would be useless to me.

Sometimes, I have more than one paper in mind when I am running a particular experiment. More often, when writing a paper, I discover the need to write different one involving the same dataset (Shhh. Don’t tell Jeremy Fox that I do this.) I research in a teaching institution, and things often happen at a slower pace than at the research institutions which are home to most “open science” advocates. Believe it or not, there are some key results from a 15-year old dataset that I am planning to write up in the next few years, whenever I have the chance to take a sabbatical. This dataset has already been featured in some other papers.

One of the standard arguments for publishing raw datasets is that the lack of full data sharing slows down the progress of science. It is true that, in the short term, more and better papers might be published if all datasets were freely downloadable. However, in the long term, would everybody be generating as much data as they are now? Speaking only for myself, if I realized that publishing a paper would require the sharing of all of the raw data that went into that paper, then I would be reluctant to collect large and high-risk datasets, because I wouldn’t be sure to get as large a payoff from that dataset once the data are accessible.

Science is hard. Doing science inside a teaching institution is even harder. I am prone isolation from the research community because of where I work. By making my data available to others online without any communication, what would be the effect of sharing all of my raw data? I could either become more integrated with my peers, or more isolated from them. If I knew that making my data freely downloadable would increase interactions with others, I’d do it in a heartbeat. But when my papers get downloaded and cited I’m usually oblivious to this fact until the paper comes out. I can only imagine that the same thing could happen with raw data, though the rates of download would be lower.

In the prevailing culture, when data are shared, along with some other substantial contributions, that’s standard grounds for authorship. While most guidelines indicate that providing data to a collaborator is not supposed to be grounds for authorship, the current practice is that it is grounds for authorship. One can argue that it isn’t fair nor is it right, but that is what happens. Plenty of journals require specification of individual author contributions and require that all authors had a substantial role beyond data contribution. However, this does not preclude that the people who provide data do not become authors.

In the culture of data ownership, the people who want to write papers using data in the hands of other scientists need to come to an agreement to gain access to these data. That agreement usually involves authorship. Researchers who create interesting and useful data – and data that are difficult to collect – can use those data as a bargaining chip for authorship. This might not be proper or right, and this might not fit the guidelines that are published by journals, but this is actually what happens.

This system is the one that “open science” advocates want to change. There are some databases with massive amounts of ecological and genomic data that other people can use, and some people can go a long time without collecting their own data and just use the data of others. I’m fine with that. I’m also fine with not throwing my data in to the mix.

My data are hard-won, and the manuscripts are harder-won. I want to be sure that I have the fullest opportunity to use my data before anybody else has the opportunity. In today’s marketplace of science, having a dataset cited in a publication isn’t much credit at all. Not in the eyes of search committees, or my Dean, or the bulk of the research community. The discussion about the publication of raw data often avoids tacit facts about authorship and the culture of data ownership.

To be able to collect data and do science, I need grant money.

To get grant money, I need to give the appearance of scientific productivity.

To show scientific productivity, I need to publish a bunch of papers.

To publish a bunch of papers, I need to leverage my expertise to build collaborations.

To leverage my expertise to build collaborations, I need to have something of quality to offer.

To have something of quality to offer, I need to control access to the data that I have collected. I don’t want that to stop after publication.

The above model of scientific productivity is part of the culture of data ownership, in which I have developed my career at a teaching institution. I’m used to working amicably and collaboratively, and the level of territoriality in my subfields is quite low. I’ve read the arguments, but I don’t see how providing my data with no strings attached would somehow build more collaborations for me, and I don’t see how it would give me any assistance in the currency that matters. I am sure that “open science” advocates are wholly convinced that putting my data online would increase, rather than constrict opportunities for me. I am not convinced, yet, though I’m open to being convinced. I think what will convince me is seeing a change in the prevailing culture.

There is one absurdity to these concerns of mine, that I’m sure critics will have fun highlighting. I doubt many people would be downloading my data en masse. But, it’s not that outlandish, and people have done papers following up on my own work after communicating with me. I work at a field site where many other people work; a new paper comes out from this place every few days. I already am pooling data with others for collaborations. I’d like to think that people want to work with me because of what I can bring to the table other than my data, but I’m not keen on testing that working hypothesis.

Simply put, in today’s scientific rewards system, data are a currency. Advocates of sharing raw data may argue that public archiving is like an investment with this currency that will yield greater interest than a private investment. The factors that shape whether the yield is greater in a public or private investment of the currency of data are complicated. It would be overly simplistic to assert that I have nothing to lose and everything to gain by sharing my raw data without any strings attached.

While good things come to those who are generous, I also have relatively little to give, and I might not be doing myself or science a service if I go bankrupt. Anybody who has worked with me will report (I hope) that am inclusive and giving with what I have to offer. I’ve often emailed datasets without people even asking for them, without any restrictions or provisions. I want my data to be used widely. But even more, I want to be involved when that happens.

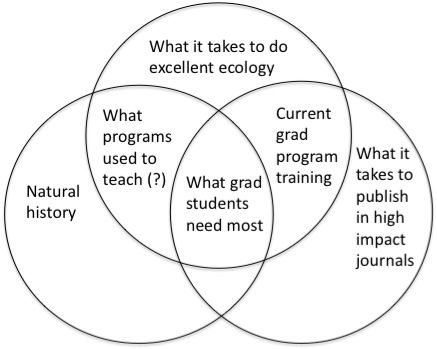

Because I run a small operation in a teaching institution, my research program experiences a set of structural disadvantages compared to colleagues at an R1 institution. The requirement to share data levies the disadvantage disproportionately against researchers like myself, and others with little funding to rapidly capitalize on the creation of quality data.

To grow a scientific paper, many ingredients are required. As grass grows the cow, data grows a scientific paper.

In Open Range, the resource in dispute is not the grass, but the cows. The bad guy ranchers aren’t upset about losing the grass, they just don’t want these interlopers on their land. It’s a matter of control and territoriality. At the moment, the status quo is that we run our own labs, and the data growing in these labs are also our property.

When people don’t want to release their data, they don’t care about the data itself. They care about the papers that could result from these data. I don’t care if people have numbers that I collect. What I care about is the notion that these numbers are scientifically useful, and that I wish to get scientific credit for the usefulness of these numbers. Once the data are public, there is scant credit for that work.

It takes plenty of time and effort to generate data. In my case, lots of sweat, and occasionally some venom and blood, is required to generate data. I also spend several weeks per year away from my family, which any parent should relate with. Many of the students who work with me also have made tremendous personal investments into the work as well. Generating data in my lab often comes at great personal expense. Right now, if we publicly archived data that were used in the creation of a new paper, we would not get appropriate credit in a currency of value in the academic marketplace.

When a pharmaceutical company develops a new drug, the structure of the drug is published. But the company has a twenty year patent and five years of exclusivity. It’s widely claimed – and believed – that without the potential for recouping the costs of work in developing medicines that pharmaceutical companies wouldn’t jump through all the regulatory hoops to get new drugs on the market. The patent provides incentive for drug production. Some organizations might make drugs out of the goodness of their hearts, but the free market is driven by dollars. An equivalent argument could be wagered for scientists wishing for a very long time window to reap the rewards of producing their own data.

In the United States, most meat that people consume doesn’t come from grass on the prairie, but from corn grown in an industrial agricultural setting. Likewise, most scientific papers that get published come from corn-fed data produced by a laboratory machine designed to crank out a high output of papers. Ranchers stay in business by producing a lot of corn, and maximizing the amount of cow tissue that can be grown with that corn. Scientists stay in business by cranking out lots of data and maximizing how many papers can be generated from those data.

Doing research in a small pond, my laboratory is ill equipped to compete with the massive corn-fed laboratories producing many heads of cattle. Last year was a good year for me, and I had three papers. That’s never going to be able to compete with labs at research institutions — including the ones advocating for strings-free access to everybody’s data.

The movement towards public data archiving is essentially pushing for the deprivatization of information. It’s the conversion of a private resource into a community resource. I’m not saying this is bad, but I am pointing out this is a big change. The change is biggest for small labs, in which each datum takes a relatively greater effort to produce, and even more effort to bring to publication.

So far, what I’ve written is predicated on the notion that researchers (or their employers) actually have ownership of the data that they create. So, who actually owns data? The answer to that question isn’t simple. It depends on who collected it, who funded the collection of the data, and where the data were published.

If I collect data on my own dime, then I own these data. If my data were collected under the funding support of an agency (or a branch of an agency) that doesn’t require the public sharing of the raw data, then I still own these data. If my data are published in a journal that doesn’t require the publication of raw data, I still own these data.

It’s fully within the charge of NIH, NSF, DOE, USDA, EPA and everyone else to require the open sharing of data collected under their support. However, federal funding doesn’t necessarily necessitate public ownership (see this comment in Erin McKiernan’s blog for more on that.) If my funding agency, or some federal regulation, requires that my raw data be available for free downloads, then I no longer own these data. The same is true if a journal has a similar requirement. Also, if I choose to give away my data, then I no longer own them.

So, who is in a position to tell me when I need to make my data public? My program officer, or my editor.

If you wish, you can make it your business by lobbying the editors of journals to change their practices, and you can lobby your lawmakers and federal agencies for them to require and enforce the publication of raw datasets.

I think it’s great when people choose to share data. I won’t argue with the community-level benefits, though the magnitude of these benefits to the community vary with the type of data. In my particular situation, when I weigh the scant benefit to the community relative to the greater cost (and potential losses) to my research program, the decision to stay the course is mighty sensible.

There are some well-reasoned folks, who want to increase the publication of raw datasets, who understand my concerns. If you don’t think you understand my concerns, you really need to read this paper. In this paper, they had four recommendations for the scientific community at large, all of which I love:

-

Facilitate more flexible embargoes on archived data

-

Encourage communication between data generators and re-users

-

Disclose data re-use ethics

-

Encourage increased recognition of publicly archived data.

(It’s funny, in this paper they refer to the publication of raw data as “PDA” (public data archiving), but at least here in the States, that acronym means something else.)

And they’re right, those things will need to happen before I consider publishing raw data voluntarily. Those are the exact items that I brought up as my own concerns in this post. The embargo period would need to be far longer, and I’d want some reassurance that the people using my data will actually contact me about it, and if it gets re-used, that I have a genuine opportunity for collaboration as long as my data are a big enough piece. And, of course, if I don’t collaborate, then the form of credit in the scientific community will need to be greater than what happens now, which is getting just cited.

The Open Data Institute says that “If you are publishing open data, you are usually doing so because you want people to reuse it.” And I’d love for that to happen. But I wouldn’t want it to happen without me, because in my particular niche in the research community, the chance to work with other scientists is particularly valuable. I’d prefer that my data to be reused less often than more often, as long as that restriction enabled me more chances to work directly with others.

Scientists at teaching institutions have a hard time earning respect as researchers (see this post and read the comments for more on that topic). By sharing my data, I realize that I can engender more respect. But I also open myself up to being used. When my data are important to others, then my colleagues contact me. If anybody feels that contacting me isn’t necessary, then my data are not apparently necessary.

Is public data archiving here to stay, or is it a passing fad? That is not entirely clear.

There is a vocal minority that has done a lot to promote the free flow of raw data, but most practicing scientists are not on board this train. I would guess that the movement will grow into an establishment practice, but science is an odd mix of the revolutionary and the conservative. Since public data archiving is a practice that takes extra time and effort, and publishing already takes a lot work, the only way will catch on is if it is required. If a particular journal or agency wants me to share my data, then I will do so. But I’m not, yet, convinced that it is in my interest.

I hope that, in the future, I’ll be able to write a post in which I’m explaining why it’s in my interest to publish my raw data.

The day may come when I provide all of my data for free downloads, but that day is not today.

I am not picking up a gun in this range war. I’ll just keep grazing my little herd of cows in a large fragment of rainforest in Sarapiquí, Costa Rica until this war gets settled. In the meantime, if you have a project in mind involving some work I’ve done, please drop me a line. I’m always looking for engaged collaborators.