I’m an Associate Professor at a regional state university. How did I get here? What choices did I make that led me in this direction? This month, a bunch of folks are telling their post-PhD stories, led by Jacquelyn Gill. (This group effort constitutes a “blog carnival.”) Here’s my contribution.

I went to grad school because I loved to do research in ecology, evolution and behavior. I knew when I started that I’d be better off having been (meagerly) employed for five years to get a PhD.

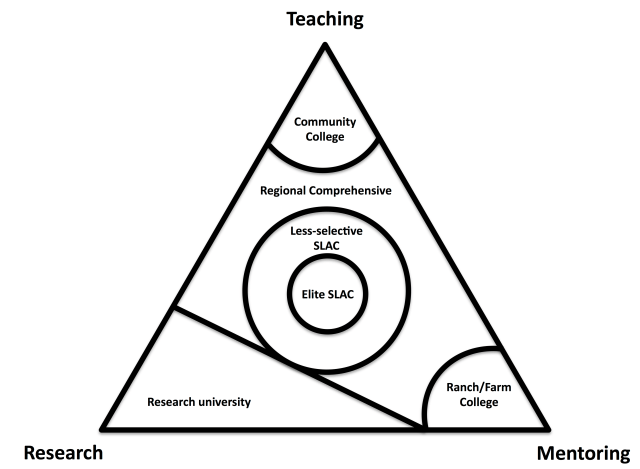

The default career mode, at least at the time, was that grad students get a postdoc and then become a professor. It was understood that not everybody would want to, or be able to, follow this path. But is still the starting place in any discussion of post-PhD employment. As time progressed in grad school, I came to the conclusion that I didn’t want to run a lab at a research university, and that I wanted an academic position that combined research, teaching and some outreach.

I liked the idea of working at an R1 institution, but there were three dealbreakers. First, I didn’t want the grant pressure to keep my people employed and to maintain my own security of employment. Second, I wanted to keep it real and run a small lab so that I could be involved in all parts of the science. I didn’t want to be like all of the other PIs that only spent a few days in the field and otherwise were computer jockeys managing people and paper. Third, I was taught in grad school that the life of an R1 PI is less family-friendly than a faculty position at a non-R1 institution. In hindsight, now that I have worked at a few non-R1 institutions, I can tell you that these reasons are total bunk. I was naïve. My reasons for avoiding R1 institutions were not valid and not rooted in reality. Even though I now realize my reasons at the time were screwed up, I was primarily looking for faculty jobs at liberal arts colleges and other teaching-centered institutions.

We muddled through a two-body problem. My spouse wasn’t an academic, but needed a large city to work. She was early enough in her career that she was prepared to move for me while I did the postdoc job hop. I wouldn’t have wanted her to uproot from a good situation. In hindsight, our moves ended up being beneficial for both of us.

As I was approaching the finish to grad school, I was getting nervous about a job. My five years of guaranteed TA support were ending. I recall being very anxious. I landed a postdoc, though the only drawback was starting four months before defending my thesis. I moved from Colorado to Texas for my postdoc, and spent the day on the postdoc and the evenings finishing up my dissertation. As a museum educator, my spouse quickly found a job in the education department at the Houston Museum of Nature and Science.

While I was applying for postdocs, I also applied for faculty positions, even though I was still ABD. And surprisingly enough, I got a couple interviews. (I think I had 2-3 pubs at the time, one of which was in a fancy journal.) I got offered a 2-year sabbatical replacement faculty position at Gettysburg College, an excellent SLAC in south central Pennsylvania. At the same time, my spouse was deciding to go to grad school for more advanced training in museum education. By far, the best choice for her was to study at The George Washington University (don’t forget the ‘The’) in Washington, D.C. This seemed like a relatively magical convergence. With uncertainty for long-term funding in my postdoc (and also no shortage of problems with the project itself), we bailed on Texas and headed back east.

We lived in Frederick, Maryland. Which at the time was the only real city between Washington DC and Gettysburg. (Since then, I’ve heard it’s been converted into an exurb of DC.) I drove past the gorgeous Catoctin mountains every day to go to work, and she took car/metro into DC to work and started grad school. We scheduled her grad school so that she’d finish up when my two-year stint at Gettysburg would be over. I taught a full courseload for the first time, and noticed that I really liked the teaching/research gig at a small college. Grad school was great for my spouse. Life was good. In my first year as a Visiting Assistant Professor, I got four tenure-track job interviews.

Through a magical stroke of fortune, I got a tenure-track job offer in my wife’s hometown, in San Diego, just 2 to 5 hours away from my family in LA (depending on traffic). The only catch was that I’d have to leave my position at Gettyburg one year early, and my wife had one year left in grad school. But, I really needed to focus on starting out my tenure-track position, and she really had to focus on grad school. She could move to DC instead of splitting the commute with me, and I could figure out San Diego without her for a year. If kids were involved, this scenario would have been a lot more complicated. If my spouse’s career was at a more advanced stage, the move from grad school to postdoc to temporary faculty to tenure-track faculty would have a lot messier and would have required more compromises. But somehow we made it work and it felt something resembling normal.

Then, after working in San Diego for seven years, we moved up to Los Angeles. I already have told that story. Which, if you haven’t read it, is a nail-biter.

As I tell the story to non-academics, they find our peregrinations rather surprising. From LA, to Boulder, to Houston, to Maryland, to San Diego, and eventually back to LA, at least for the last seven years. (In the meanwhile, I’ve been going back and forth from my field site Costa Rica on a regular basis). This frequency of moving is entirely normal in academia, even if we look like vagabonds among our friends.

What do I offer as the take-home interpretations of my post-PhD job route?

First: The geography of my tenure-track job offers was lucky. To some extent, I’ve made this luck through persistence, but having landed a job in my wife’s hometown was pretty damn incredible. And after botching the first one entirely, getting one in my hometown was amazing. Now that my spouse is at the senior staff level, openings in her specialized field of museum education are about as rare and prized as in my own field. However, we now live in a big city with many universities and many world-class museums, so we can (theoretically) move jobs without moving our home. We now are juggling a three-body problem.

Second: My early choices constrained later options. Even though I no longer am wary of an R1 faculty position, after spending several years at teaching-focused universities that is a long shot for me. (I do several people who made that move, but it’s still a rarity.) I’m confident that I can operate a helluva research program at a highly-ranked R1, but I’m too senior for an entry-level tenure-track position, and not a rockstar who will be recruited for a senior-level hire. For example, I am confident that I would totally kick butt at UCLA just up the road, but I doubt a search committee there will reach the same conclusion. I am just as pleased to be at a non-prestigious regional university, and when I do move, it’ll be because I’ll be looking for better compensation and working conditions. I’m looking at working at all kinds of universities, and I think my job satisfaction will be more tied to local factors on an individual campus rather than the type of institution.

Third: I applied for jobs that many PhD students and postdocs think are unsuitable for themselves. I spent a lot of time creating applications for universities that I’ve never heard of. I was hired as an “ecosystem ecologist” at CSU Dominguez Hills in Los Angeles. Even though I grew up in Los Angeles, the first time I ever heard of CSU Dominguez Hills is when I saw the job ad. And I’m not an ecosystem ecologist either. That didn’t keep me from spending several hours tailoring my application for this particular job. But I wouldn’t have gotten this job unless I applied, and most postdocs are not applying for jobs like the one I have now. I know this from chairing a search committee for two positions last year. That’s a whole ‘nother story.

Fourth: Is being a professor my most favorite job ever? Actually, no. My employment paradise would be a natural history museum, with a mix of research, outreach and occasional teaching. I’m not a systematist or an evolutionary biologist, so getting hired into this kind of job is not likely. However, I have had a couple interviews for curatorial-esque positions over the last ten years and was exceptionally bummed that I didn’t get them. On the balance, even large museums go through phases of financial instability. It would be hard to give up tenure for a job that might bounce me to the street because of the financial misdeeds of board members and museum leadership. I’ve seen too many talented good museum people lose positions due to cutbacks or toxic administrators. I don’t know what could get me to take off the golden handcuffs of tenure. There are some university museums that hire faculty. That would be wonderful. Maybe someday that could happen. But I am pleased with what I’m doing, and I still am amazed that there are people paying me to do what I love.

Fifth: I ruled out a number of possibilities for family reasons. There are a variety of locations where I would be able to find work but would be unworkable for my spouse. Even in the depth of a job crisis, I opted against a number of options that would’ve given me strong and steady employment.

Sixth: I am not employed as a professor because I deserve it more than others. There are others equally, and more, deserving that are underemployed compared to my position in the academic caste system. The CV I had when I got my first academic position probably wouldn’t be able to do so now, 15 years later.